Stephen Weber’s SDSU Legacy

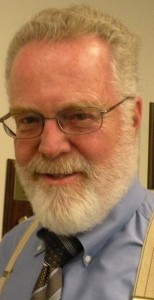

Stephen Weber’s 15-Year Legacy at San Diego State

Major accomplishments and disappointments

By Manny Cruz

Educated as a philosopher, Stephen L. Weber never intended to become a university president. Yet here he is, 42 years after receiving his Ph.D. in philosophy from the University of Notre Dame, capping a 15-year stint as president of San Diego State University and set to retire to the home near Bar Harbor, Maine, where he and his wife, Susan, raised two sons.

For Weber, a conspicuous presence on campus with his finely manicured white beard and philosopy professor appearance, those 15 years have been filled with great achievements, some tragedies and a seemingly endless struggle with a host of issues, not the least of which have been continuous funding cutbacks and trying to ensure that each of the campus’ 31,000 or so students reach their highest potential.

Weber began his career as a faculty member and philosopher at the University of Maine. “That’s what I thought I was going to do,” he says. But after getting involved in the University Center, he was asked to replace the university president’s assistant, who was leaving the post. His response: “No, I have integrity.” Nudged by a colleague, Weber took the post, forever sealing his future as an educator-turned-administrator on higher education campuses. That path led him to become president of State University of New York’s Oswego campus, interim provost of SUNY, vice president of academic affairs at St. Cloud State University in Minnesota and dean of arts and sciences at Fairfield University in Connecticut.

Asked during an interview why he is retiring now, Weber, 69, says simply, “Because I’m old.” (The average age of university presidents, according to various studies, is about 60). Weber’s self-deprecating response doesn’t tell the whole story, though. “Susan and I had mindlessly thought that we would retire when I was 65,” he says. “But you do this without really thinking. When I was 30, I said I want to retire when I’m 65. As we got to 65, a lot of my colleagues said, ‘Don’t retire yet, you’re obviously having a good time.’ And they were right. So I said, OK.”

Weber spent an hour with SD METRO recently offering up some of his most important accomplishments and disappointments during his long tenure at San Diego State.

Q. What are the things you are most proud of during your 15-year tenure here?

A. Well, let me make it clear that they weren’t accomplished by me but I’m really pleased to be associated with the accomplishments and probably the one that I’m most proud of is the increase in the graduation rates. Our trade journal, The Chronicle of Higher Education, did an article about three or four months ago and it showed that San Diego State led the nation in improving the graduation rates. We were up by 17 percentage points over six years — points not just percentages —and the closest to us were tied for second and third, they were up 12 percentage points. Blew the field away. Beyond that, the story does not capture that over 10 years, our graduation rates increased 28 percentage points, and our students of color are up 31.2 percentage points in their graduation rates. So, while the achievement gap is growing in the rest of the country, San Diego State is down to about 2 percent between students of color.

Q. What are the reasons for the increase in the graduation rates of students of color?

A. A lot of hard work by a lot of people. . . We’ve developed 26 different programs designed to work for our least well-prepared students. You don’t have to worry about your honors students, they’re going to do fine. It’s the ones that come from disadvantaged schools who struggle. So we got a broad number of programs that are focusing on those students. And since there is a sorry correlation between the students who come from low-income schools and students of color, that’s how we end up focusing on bringing disadvantaged students up, that brings up the students of color.

Q. What kind of programs?

A. One of the first things we did, we made orientation mandatory. For a lot of these students, they would come from families that didn’t talk about university experience around the kitchen table because the parents haven’t had that experience. . . We have a program called EOP, Education Opportunity Program. More than 4,000 low-income students in that program. Biggest one in the state of California. It’s a program that wraps all sorts of support and tutorial services around low-income students and these low-income students from disadvantaged schools actually out-perform the rest of the student body.

We also reached out into the South Bay with our Compact with Success program with Sweetwater (Union School District) to try and get these students better prepared while they are still in high school, and our programs in City Heights — we run three schools in City Heights with about 5,000 students in them, an elementary school, a middle school and a high school.

One of the things we’ve discovered is students who live in residence halls are much more likely to graduate than students who don’t, and the data is quite clear about that. So we try to put together a package that makes it possible for low-income students to live in residence halls, try to raise more scholarship money and in doing things like that.

Q. What is the percentage of minority students at State?

A. The overall percentage (of students from diverse ethnic and racial backgrounds) is roughly 50 percent. I think it’s about 52 percent now. The largest segment of our students of color is our Hispanic students. They’re roughly again, 25 percent.

Q. Any major disappointments in the 15 years?

A. (Laughs) Yeah! Lots of disappointments! The biggest disappointment I’ve had is that we haven’t been able to really improve California’s schools, K-12. nd the university has a responsibility to try to do that, that’s why we’re in Sweetwater, that’s why we’re in City Heights. We do a lot of research on educational outcomes. We provide some of the very best work in the country in terms of educational reform.

Q. When you look at statistics, they say that we, as a country, have fallen behind in education. Is that all part of it, the K-12?

A. Well, there are a lot of reasons for what goes on. I mean, we’re not investing in ourselves and our society’s future and schools are part of that. Back in the ’60s and into the ’70s, California was among the best K-12 systems in the country if you look at the figures there, consistently on every score in the top five states in the country. Now, on every score, (we’re among) the worst five states in the country. It’s brutal. So, the first thing to understand is California is losing the competition to the rest of the United States and the United States is losing the competition to the rest of the world. It’s a very sad picture. And it’s confounded by the fact that we delude ourselves into thinking that we’re going to be a high-tech society when we’re not developing our students to be a high-tech society.

Q. Are you getting a lot of requests for admission from places like India and China?

A. If memory serves, we have about 1,600 international students from all over the world including India and China. If you look at higher education across the United States, 40 years ago, almost all our graduate students were in science and engineering. Twenty years ago, the majority had already begun to flip to non-native born, partly because our schools weren’t good enough to prepare them to move into graduate programs in science and engineering. But 20 years ago, even though we had so many foreign-born student engineers, they stayed in this country, because this country offered opportunities. But, now what’s happening is that China and India are offering opportunities and the growth rates there of course are phenomenal. But it means we’re losing a lot of those people back to their native countries where 20 years ago they stayed here and founded Google and things like that.

Q. California once had the premier educational system in the country. Now here we sit in 2011 and realize that California has fallen off the track. Is that because of lack of funding by the state? What has caused this decline?

A. There are a lot of things that have caused the decline. First of all, the failure of will — we gave up. We’re comfortable, the classic thing you can see in the family sometimes. You have generations that work really hard and then you finally want to enjoy the fun and not work so hard. I never saw it coming. As a young man, we were eager to be the lead dog. Time and time again now, you say —not so much. . . Now, we’re passing debt charges. That’s just hardly defensible at all. California in particular, we’re not investing in education. In the California State University system, we had big cuts the year before last, a bigger cut this year, bigger cuts still next year. But we’re not investing in other parts of our society either. We’re just giving up and, strangely enough, a lot of the people who are giving up claim that they love the society. I don’t understand that.

Q. Do you consider yourself a philosopher?

A. Oh, yeah. First and foremost. I don’t consider that there’s anything magical about philosophy because I don’t think philosophy is the way to go if you are going to be a university president. I think every discipline brings different fruits to bear to the presidency. I have a good friend, Gordon Holland. When I was assistant to the president, Gordon was dean of the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Maine. He went off to be the president of the University of New Hampshire and then took over the presidency of Gettysburg College. Gordon was a psychologist specializing in small group behavior. So everybody’s got something that they’re good at because of the disciplines they studied. In my case, the fundamental philosophy goes all the way back to Socrates’ “know what you don’t know.” People get screwed up because they think they know things they don’t know. And hubris takes over and they push on. I’ve been very good about recognizing that I don’t have the answer to that and good people around me who I trust, as advisers, and they serve San Diego State very well.

Q. What is the toughest thing you’ve had to do?

A. Different things are tough in different ways. One of the toughest things I had to confront was the murder of the three engineers shortly after I came. The whole institution was traumatized by that and I was new in the role, and yet I had to speak on behalf of the university and comfort colleagues who were shocked and families who were shocked. The other was dealing with the endless budget withdrawals from the state of California and to be able to do that because we’ve been very entrepreneurial as a university and able to do that in a way that hasn’t done permanent damage to the university. Whether they’ll keep that up or not, I don’t know. We made a lot of progress in spite of loss of resources.

Q. Will Maine become your permanent home from now on?

A. Yeah, but I should say that we’ve never retired before so we’re not quite sure how it’s going to play out, but our plan is that we will stay in Maine until about Thanksgiving every year and then we’ll travel to a warm place for a couple of months. This year we are going to the south island in New Zealand for December and January and then we’ll come back to San Diego for February and March and then back to Maine.