The prophecy and the perils of price controls: Three economic assessments

With grocery prices stubbornly high and the packages selling the products reduced – nicknamed “shrinkflation” – there’s a chance the United States will see price controls on food if Vice President Kamala Harris wins the presidency – a first in more than 50 years.

Appearing to pick up where President Joe Biden left off, when, in February, he complained “many corporations in America (are) ripping people off: price gouging, junk fees, greedflation, shrinkflation,” in August, while campaigning for her boss’s job, Harris said the remedy includes price controls on food.

The plan, according to her campaign, is “the first-ever federal ban on price gouging on food and groceries – setting clear rules of the road to make clear that big corporations can’t unfairly exploit consumers to run up excessive corporate profits on food and groceries,” says one published report.

Background

Five months before the Vice President’s announcement, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) released a report, entitled “Feeding America in a Time of Crisis: The United States Grocery Supply Chain and the COVID-19 Pandemic,” which said, “Grocery retailer profits rose and remain elevated, warranting further consideration by the Commission and policymakers.”

“Specifically, food and beverage retailer revenues increased to more than 6% over total costs in 2021, higher than their most recent peak, in 2015, of 5.6%,” the FTC’s report said. “In the first three quarters of 2023, retailer profits rose even more, with revenue reaching 7% over total costs.

“These elevated profit levels warrant further inquiry by the Commission and its policymakers,” the FTC added.

The FTC says its study is based on information it subpoenaed from Kroger, Walmart and Amazon.

One of the FTC’s concerns, according to people familiar with the Commission, is a possible violation of the Robinson-Patman Act. A federal law passed in the 1930s, it prohibits distributors and manufacturers from providing discounts or kickbacks to one client but not others in the same industry.

The concern is that discounts or kickbacks could provide one retailer – in this case, a grocer – an advantage over others.

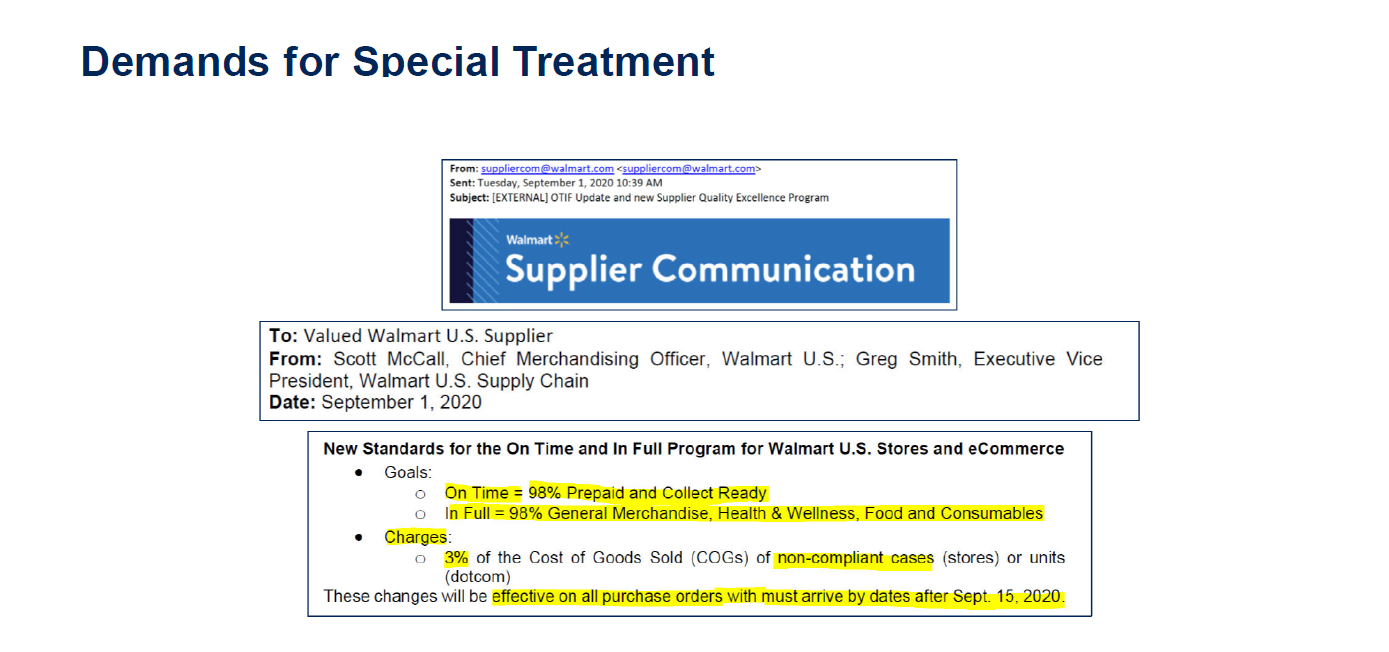

The National Grocers Association (NGA), an industry group of about 20,000 independent grocery stores, provided SD METRO with information it says shows Walmart requested and received special treatment from some of its food suppliers during COVID-19, which possibly violated the Robinson-Patman Act.

The email, from two Walmart executives, Scott McCall and Greg Smith, dated Sept. 1, 2020, tells their suppliers in the United States they need to fulfill 98% of the orders Walmart places with all purchases arriving after Sept. 15, 2020.

The email, from two Walmart executives, Scott McCall and Greg Smith, dated Sept. 1, 2020, tells their suppliers in the United States they need to fulfill 98% of the orders Walmart places with all purchases arriving after Sept. 15, 2020.

McCall and Smith are no longer with Walmart and couldn’t be reached for comment. Walmart spokesperson Molly Blakeman didn’t respond to SD METRO’s requests for comment on the issue.

As the NGA’s Christopher Jones sees it, large retailers, like Walmart, received discounts from their suppliers which their members didn’t receive. As a result, NGA’s members were forced to charge their customers more for similar products, especially food.

Price Controls, 1971 – 1974

The last U.S. president to implement price controls was Richard Nixon in August 1971, much of it due to prices increasing at their fastest pace since the Korean War. Prior to Nixon, there were price controls on food, as well as rationing, during World War II.

Nixon established the Cost of Living Council, which consisted of the Treasury, Agriculture, Commerce and Labor secretaries as well as Arthur Burns, the chairman of the Federal Reserve and others, including the director of the Office of Management and Budget, Chairman of the Council of Economic Advisors, the Director of Emergency Preparedness and the Special Assistant to the President for Consumer Affairs.

Its day-to-day activities were directed by Donald Rumsfeld, later the secretary of defense under Presidents Gerald Ford and George W. Bush.

The Council’s charge was to “develop and recommend … policies, mechanisms, and procedures to maintain economic growth without inflationary increases in prices, rents, wages, and salaries.”

At the time, inflation in the United States was 4.62%. Two years later, it was over 7% and by the time President Nixon left office, in August 1974, due to the Watergate scandal, it was around 11%.

Nixon expanded the use of price controls in March 1973, announcing limits on meat prices, saying, in a televised address, “With the help of the housewife and the farmer, they (prices) can and should go down.”

“Food prices in general and meat prices in particular have been rising rapidly and have reached record levels in many cases,” The New York Times reported.

To make sure consumers were aware of the new price controls, then-Treasury Secretary George Shultz, The Times reported, said there would be a “prominent display of lists of ceiling prices in stores, spot checks by the Internal Revenue Service and investigations by the service in response to consumer complaints.”

The Efficacy of Price Controls

“They’re always terrible,” said Duke University Economics Professor Connel Fullenkamp. “It’s another one of those well-intentioned bad ideas.”

During Nixon’s time in office, he said, “The economy was overheating, and they were attempting to restrain wage and price growth at a time when demand for labor was going up.

“It seemed like a good deal for employers but, of course, they couldn’t find anyone to work because they wanted higher wages. It was made worse because everyone knew it was temporary, knowing the controls would expire and they’d go back and do business as usual,” he added.

Price controls can also lead to shortages and rationing, Fullenkamp said.

“If certain suppliers get price gouging complaints and price freezes, grocery stores will attempt to diversify away from those particular suppliers and offer alternative products,” he said. “It could result in rationing with grocery stores saying, ‘We get this allocation every Thursday, and you’ve got to be the first one in the store, otherwise you’re out of luck.’”

Fullenkamp also suggested another way to define grocery stores:

“They’re middlemen,” he said. “Their profit margins are terrible, around 4%. They’re squeezed between consumers on one hand, who want low prices, and suppliers, like Proctor & Gamble, Mondelez, Kellogg’s and Kellanova, who want high margins.”

Michigan State University’s David Ortega, an economics professor focusing on food, says one reason food demand and consumption increased was because “households accumulated savings during the pandemic and couldn’t take vacations because of stay-at-home restrictions.”

Another factor was equally important.

“The fiscal stimulus from the 2021 American Rescue Plan (and in 2020, the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act) reached many households and injected a lot of cash into the economy,” he said. “One area where households could splurge was on groceries. So, the reason we’ve seen such significant increases in food prices is because we’ve had this combination of supply-side shocks but also demand factors.”

As for whether grocery store profit margins have increased sizably, Ortega said, “It’s important to look at other measures of profitability. Things like gross profit margins, so how much companies are making on goods after the cost of producing and stocking those items.

“Gross profit margins for some of these large food manufacturers and grocery stores have remained steady,” he added.

He also suggested increased gross profit margins can come about due to consumer switching.

“Consumers switched to store brands as inflationary pressures strained their household budgets. Those items have a larger profit margin than some of the national brands grocery stores sell. So that could be a contributing factor to increased gross profit margins.”

Increased fuel prices also contributed to higher grocery prices.

“Food is very energy and labor intensive to produce,” Ortega said. “Fifteen cents out of every dollar that’s spent on food is because of things that happen before the item leaves the farm.

“The majority of the costs for food are due to things that accrue after it leaves the farm, like transportation, distribution, packaging as well as the wholesale and retail trade,” he added.

As for price controls, Ortega said, “A price ceiling on food that’s below market equilibrium (where supply meets demand and prices are stable) will lead to demand outpacing supply and, thus, shortages. But that’s not the full story:

“Companies could cut corners because they can’t increase prices. You could see them use inferior ingredients, plus more shrinkflation or skimpflation, he added.

Economist Christopher Thornberg, a founding partner of Los Angeles-based Beacon Economics, said, “The U.S. economy is incredibly competitive. And so the concept that corporations could just willy-nilly crank up prices just because they can, what planet do you live on?

“If you think food prices are up because supermarkets are gouging people, then you would see an enormous increase in supermarket profits. I’m sorry, supermarkets are barely making money – they’re getting hammered,” he added.

Thornberg also said consumers made substitutions, spending less at grocery stores and supermarkets and more at restaurants over the last three years.

“Restaurant prices went up by 6.2% over the last three years, and restaurant prices increased about 20%, give or take, more than supermarkets,” he said. “Restaurant consumption went up 3% a year every year over the past three years.

“What we’re talking about is the wealth effect,” he said.

“There have been enormous increases in asset prices, enormous increases in incomes and people are living it up,” he said. “If people were really getting clobbered by food prices, they’d be consuming less at restaurants and more in supermarkets.

“The data doesn’t support it. Not only is it a narrative that contradicts economic theory as we know it, it’s also a narrative completely contradicted by every bit of data we have,” Thornberg added.