Big-Box, Online and the Smaller One: The Mishmash of Food Retailing in the Post-Pandemic, Inflationary Economy

The country’s more than 96,000 grocery stores and supermarkets, generating about $1.1 trillion in annual revenue, are undergoing a metamorphosis attributed to events they never expected – a global pandemic and inflation – leaving them vulnerable to being bushwhacked by financially formidable competitors and acquired, too.

That’s the case with Winn-Dixie and Harveys supermarkets, once owned by Southeastern Grocers. German discount grocer Aldi, a privately held company with more than 2,000 stores in the United States, purchased the Jacksonville, Fla.-headquartered entity in March, picking up nearly 400 stores in Florida, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi and Louisiana. Financial details were not released.

Closer to San Diego is the potential merger between two grocery entities, Kroger and Albertsons, which the Federal Trade Commission attempted to stop with a lawsuit filed in U.S. District Court in Portland, Ore., saying it’s “anticompetitive,” and will lead to “higher prices for groceries and other essential household items for millions of Americans.”

The trial ended Sept. 17th, but Judge Adrienne Nelson, who oversaw it, didn’t commit to issuing her ruling on the tie-up on a particular date, saying, instead, “she would work as quickly as possible on her decision,” a published report said. There’s an expectation that she may likely issue her ruling the week of October 21.

Another trial over the merger is underway in King County Superior Court in Seattle. Washington State Attorney General Bob Ferguson filed an antitrust lawsuit against the merger, saying, according to a news release from his office, “it will severely limit shopping options for consumers and eliminate vital competition that keeps grocery prices low.”

Kroger attorney Mark Perry, in opening comments, replied the merger will help the two companies compete against larger rivals, like Walmart, Costco and Amazon, saying Kroger and Albertsons face “an existential threat” if the merger isn’t allowed, according to a published report.

A third trial against the merger, and the last one underway, recently started in Denver. The State of Colorado filed an antitrust suit against the merger. The trial started at the end of September and is being held in Denver District Court.

California Attorney General Rob Bonata is also opposed to the merger and recently sought a temporary injunction against it.

In addition to California, Colorado and Washington State, the attorneys general of Arizona, the District of Columbia, Illinois, Maryland, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon and Wyoming joined the FTC’s lawsuit against Kroger’s $24.6 billion purchase of Albertsons. The two companies have about 5,000 stores, but 579 will be sold if the merger is approved.

In February, Kroger announced it would “invest $500 million to lower prices” with its merger with Albertsons. Bloomberg News reported in August that Kroger would cut grocery prices by $1 billion if the merger goes through. Phone calls and emails to Kroger and Albertsons about the merger weren’t immediately returned.

Given recent trends – people attempting to extend their food budgets by shopping at large, discount grocers due to heightened prices – neighborhood grocery stores and supermarkets around the United States could see a curt future, says a financial analyst requesting anonymity.

As David Livingston, a consultant with many years of working with grocery stores and supermarkets, sees it, today’s grocery market took root 40 years ago.

“It goes back to the ‘80s, and then, by the early ‘90s and 2000s, Walmart was in every county, city and town in the country,” he said. “And they drove a lot of stores off of Main Street and caused a lot of bankruptcies.”

“Walmart operates supercenters and hypermarkets as does Costco so, originally, groceries were sold there to increase basket size (the number of items a consumer buys), but now they sell a significant number of groceries, so they’re a true competitor,” said Joseph Welsh, a Las Vegas-based grocery consultant, also known as “Joe the Grocer,” whose industry experience started 46 years ago, when he was 13.

He recently testified at the trial about the Kroger-Albertsons merger in Seattle.

“Ninety percent of America lives within 10 miles of Walmart,” Molly Blakeman, the company’s spokesperson, told SDMETRO. “We serve about 145 million customers a week in the United States, and (during COVID-19) online pickup and delivery really took off in the grocery space.”

Where Grocery Dollars Are Spent

Between March 2020, when the pandemic closed many offices and schools across the United States, and last year, Walmart’s annual grocery revenues jumped from $208.4 billion to $264.2 billion, an increase of nearly 27%. The company generated almost 25% of all “food-at-home” spending in 2023 as measured by The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), which says more than $1.1 trillion was spent for “food-at-home” in the United States in 2023, up from $1 trillion in 2022.

If last year’s grocery sales from Sam’s Club are added in, Walmart’s grocery sales grew to $320.6 billion, an increase of nearly 28% from 2020 when Walmart’s and Sam’s Club grocery revenues were a combined $250.5 billion. They could be higher, but Walmart doesn’t break out its revenues by category for its namesake stores in Mexico, Central America, Canada, China and the United Kingdom.

Walmart reports its U.S. grocery revenues for its namesake stores separately. Sam’s Clubs grocery revenues are also reported separately but not by country origin. There are over 4,600 Walmart stores and 599 Sam’s Clubs in the United States, the company says. Walmart also has 170 Sam’s Clubs in Mexico and another 44 in China.

In comparison, Walmart’s nearest U.S. competitor among supermarkets with a sizable national footprint, Kroger, with over 2,700 outlets, making it the largest supermarket chain in the United States, did $133.4 billion in 2023 in grocery sales, according to its annual report, up just over 8%, from $123 billion, in 2020.

“What’s really powerful about Walmart, whether it’s in expansionary or recessionary times, is that people need things, and we’re an everyday, low-cost retailer,” Blakeman said. “Customers are also coming to us in times where they may be a little more stressed about their finances, and we’re here to deliver, no matter the time period, no matter how they’re feeling about their wallet.”

And, indeed, consumers may have felt stressed about their finances because, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, grocery prices rose about 25% between March 2020 and August 2024.

“A lot of people perceive our customer as a lower-income American, and it is, but we also continue to gain relevancy with middle-income and higher-income customers,” Blakeman said. “Everybody likes to save money.”

Walmart isn’t the only competitive threat to the neighborhood grocery store and supermarket. Other big-box and warehouse-size retailers, plus a significant online player, too, are also taking market share.

Costco, a warehouse-size retailer offering discount prices, with 614 warehouses in the United States and Puerto Rico, saw its food and grocery sales jump to $128 billion last year, up 11.3% from 2022’s $115 billion. Costco doesn’t separate its category revenues by country origin. Food and grocery revenues constituted more than 50% of Costco’s annual revenues over each of the last three years.

Target, another discount retailer, saw its grocery revenues advance from $18.4 billion in 2020 to $24.3 billion last year, about a 32% increase. CEO Brian Cornell said in August there’s “significant opportunity for growth in that space.”

Seven years ago, Target purchased Shipt, a same-day delivery company, which allows it to deliver groceries and other products to consumers the day they’re ordered online.

Amazon doesn’t break out its grocery sales – from either its online platform or its Whole Foods subsidiary – in its annual report, but eMarketer estimates it will see about $40 billion in online grocery sales this year, up from $25 billion in 2020.

In addition to the companies mentioned, Numerator, a Chicago-based market research firm, reports that between 2020 and 2024 consumer grocery revenues also increased at Albertsons, Aldi, Dollar General, 7-Eleven, Trader Joe’s and Dollar Tree.

But food selling isn’t limited to those companies alone.

Statista points out the food retail industry is fragmented and includes “convenience stores, drug stores, mass merchandisers, and food service facilities,” plus specialty food stores, grocery stores and supermarkets, estimating they did a combined $8 trillion in food sales last year.

“Everybody sells groceries,” Welsh said. “You can buy bread, eggs and soft drinks at the convenience store. During COVID-19, some restaurants offered groceries to make their numbers.

“Then you’ve got online sellers (like Amazon) invading the space, too. Brick and mortar (grocery stores and supermarkets) is being attacked from many different directions,” he added.

The New Normal

Not only did the pandemic change shopping habits, but so did inflation. People bought items in bulk, like paper towels and toilet paper, from Walmart, Costco, and other big-box and discount retailers, while local grocery stores and supermarkets were trafficked for items that would sooner perish, like meat, vegetables, dairy, and fruit.

“That part of the store we call the ‘center store,’ and that typically relates to the non-perishable items, the club stores and dollar stores (like Walmart, Costco, and Dollar General) have taken many of those purchases out of the supermarkets and, unfortunately, those are good profit categories,” Welsh said.

The National Grocers Association (NGA), an industry group of about 21,000 independent grocery stores, sees new purchasing habits, too.

“More consumers are willing to go to dollar stores, willing to travel a little bit further to go to Walmart, are willing to look at other options on omnichannel, e-commerce type of platforms,” said Christopher Jones, NGA’s chief government relations officer.

As a result, supermarkets and grocery stores were forced to change.

“They’ve learned how to provide curbside pickup service,” Welsh said. “Some who fought online selling are engaged in it, not so much as a profit center but as a defense mechanism to prevent attrition from their store to someone else’s.”

Another consultant says the pandemic was a watershed moment for supermarket and grocery executives.

“COVID took 20 years of change and put it into two,” said Craig Rosenblum, of Columbus Consulting. “Everybody began to realize if they couldn’t provide shoppers a way to buy online, pick up in store or deliver products, they were going to lose out.”

The average grocery store is about 40,000 square feet, so he sees some of the space being repurposed for e-commerce, in-store pickup, food service, or other products that allow a grocery or supermarket to differentiate from larger competitors.

Another way grocery stores stand out is by the products offered on the store’s perimeter.

“They need quality baked goods, produce, meats, deli and seafood,” said NGA’s Jones. “Consumers often equate the quality of the store with those kinds of items, which are outside the center of the store.”

Even Walmart, says Rosenblum, is responding to its changing consumer profile by improving the look and feel of their stores and offering better produce and baked goods.

There’s an additional way to compete, too, suggests Livingston, and it might be one few consider. Consumers judge in-store grocery shopping by the entire experience, including the checkout counter.

“When you can do the whole package – competitive prices, good customer experience, good exit experience, decent parking and the other perks, like delivery – you stay competitive,” he said, adding that one of his clients wanted to install self-checkouts to save on labor costs.

“And I said, ‘I don’t think you want to do that. You’ve attracted some of the best cashiers in the city. The customer’s exit experience is going to be way better in your store compared to Walmart. If your cashier is the last person they have contact with at the store, and they leave feeling better about themselves than when they came in, you’ve accomplished your job.’”

AI and New Employees

Today’s challenges are bringing about hiring changes, too.

“Typically, the kid who was the best stocker was the one that got promoted to assistant manager,” Welsh said “Then, if he held on long enough, he’d become the store manager.”

These days, he says, grocery stores are seeking different employees, those with accounting, information technology and marketing skills.

Plus, Welsh says, because grocery stores are now adding a variety of ready-to-go meals, they may need a very different kind of talent.

“If a store had just a deli, you needed someone back there who could learn how to fry chicken, prepare French fries, stir up mashed potatoes. But when you have meal solutions that are crafted in the store or you have sushi bars, you may need a sous chef or a sushi chef to prepare those meals,” he said.

Welsh says if online selling becomes a larger part of the grocery store industry, it will need to find new and creative ways to increase foot traffic into the stores.

“Twenty or 30 years ago, we didn’t co-brand inside the store,” he said. “Today, you have Starbucks kiosks and Little Caesar’s pizza. We’re doing everything we can at the store level to keep our foot traffic up.”

Artificial intelligence, says Rosenblum, will have a role.

“It will allow executives to forecast their decisions whether they’re looking to improve margins or increase sales,” he said. “They’ll still have to guide it and provide the insight of what they’re trying to achieve.”

The German Invasion

Aldi, started as the world’s first discount grocery store in 1961 in Germany, is owned by the Albrecht family, the world’s 11th wealthiest family, says TheStreet.com.

“Right now, from a value standpoint, Aldi’s the one grocery executives need to be the most aware of,” said Rosenblum.

Aldi, which opened its first U.S. store in Iowa in 1976, has more than 2,000 stores across 36 states. It’s the world’s fourth largest grocer, with more than 13,000 stores around the globe.

The company picked up nearly 400 Winn-Dixie and Harveys supermarkets in March, with plans to convert some of them into Aldi stores over the next several years, according to a published report.

There are 16 Aldi stores in San Diego County.

Another German grocer in the United States, Lidl, with more than 150 stores between New York’s Long Island and Virginia, is also a discount operation, with more than 340,000 employees around the globe.

The Numbers

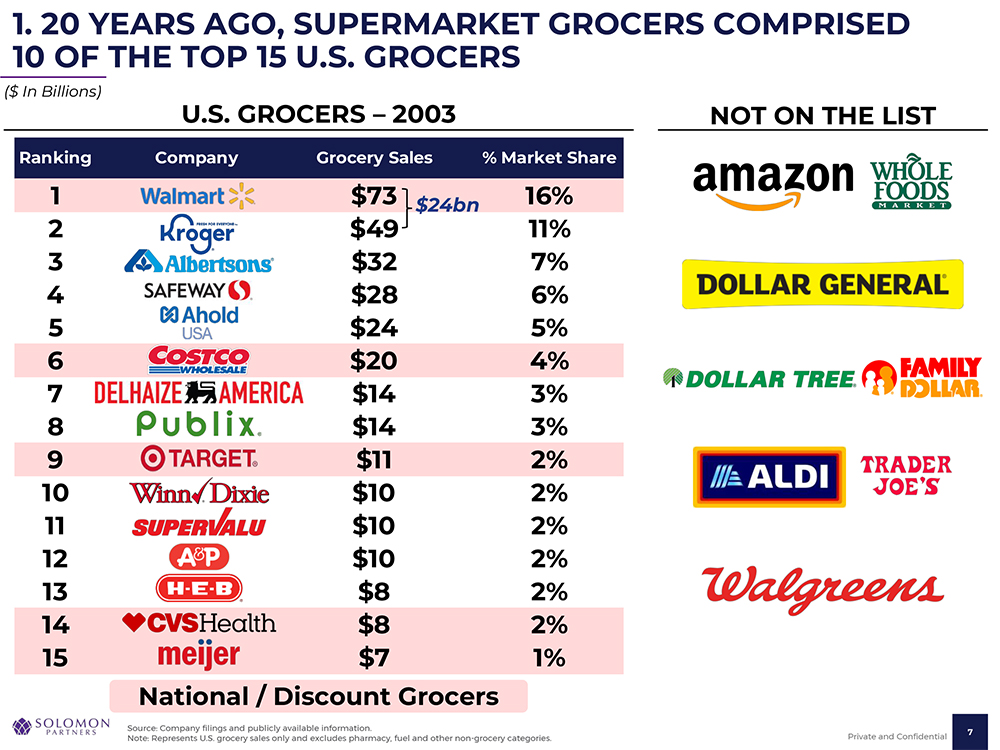

Solomon Partners’ Scott Moses, in a report about the state of the grocery industry, shows how much it’s changed over the last 20 years.

In 2003, the country’s top 10 grocers were, in order, Walmart, Kroger, Albertsons, Safeway, Ahold, Costco, Delhaize America, Publix, Target and Winn-Dixie.

Twenty years later, the top 10 players are, in order, Walmart, Kroger, Costco, Albertsons, Amazon, Target, Ahold Delhaize, Publix, Dollar General and H-E-B.

In the last four years, there’s also been sizable value changes in some of the country’s leading grocers and big-box retailers.

In late March 2020, shortly after COVID-19 struck, Amazon’s market capitalization (the value of its stock times the number of shares outstanding) was $972.91 billion. In early October 2024, it was nearly $2 trillion, growing more than two times in just over four years.

Costco, during the same time frame, went from a market capitalization of $125.91 billion to nearly $400 billion, an increase of more than three times.

Walmart saw its market capitalization double, from $321.8 billion in March 2020 to $650.62 billion in October 2024.

Target’s went from $46.57 billion to $71.88 billion, a 54% increase between March 2020 and October 2024.

Kroger’s market capitalization increased 70%, from $23.43 billion in March 2020 to just over $40 billion in October 2024, while Albertsons’ market capitalization went up about 40%, from $7.55 billion to $10.59 billion.

“Wall Street expects the biggest players to take share (from smaller grocers) and dominate the industry,” said another financial analyst requesting anonymity. “That’s how it sees where things are going.”

Value Proposition

The NGA’s Jones and Solomon Partners’ Scott Moses say the value of the local grocery store and supermarket is greater than their commercial purposes.

“What helps independent grocery stores maintain their customer base is a virtuous cycle of reinvestment in the community,” Jones said. “They’re supporting local Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts, sponsoring Little Leagues. They’re also partnering with local universities, local farmers and ranchers to get locally grown and raised products on their shelves. That’s what keeps them relevant in a market where they can’t compete in the center of the store.”

“Supermarket grocers have been pillars of thousands of American communities for generations,” wrote Moses in a report in December 2023. “But they cannot magically – without sufficient scale – continue to provide better prices, better wages and benefits, to a largely unionized employee base; offer more local and sustainable food options that support local farmers; be a community pillar; offer engaging first jobs or great careers to millions of people; and be there to sustain us in the next crisis.”