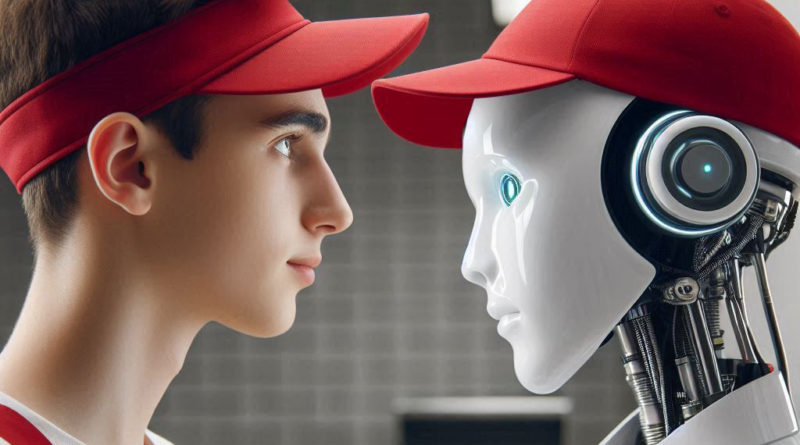

Workers vs. The Robots: Minimum Wage and California’s Fast-Food Offering

California’s new minimum wage for fast-food restaurant workers – upped April 1st to $20 an hour – impacts the Golden State’s most vulnerable workers, leaving effects that could last well beyond just a missing paycheck.

“The kids are the canaries in the coal mine,” Los Angeles-based economist Christopher Thornberg told SD METRO, referring to teenagers seeking or working summer jobs. “They’re the first to lose their jobs and not have the opportunities in part, because not only are they suffering the impact of reduced labor demand at these higher costs, but of course, equivalently, they’re replaced by adults.

“At $20 an hour, you want an adult,” he continued, because they’re not leaving to return to school or seek another employer that’s more fun, like Disneyland.

Thornberg runs Beacon Economics, a consultancy.

In a 41-page report, he and another economist, Niree Kodaverdian, write that “the increase in unemployment is almost exclusively a young person phenomenon.

“Of the nearly 130,000 newly unemployed people in the last two years, over 90% were under the age of 35. And within this age group, the hardest hit subgroup has been teenagers,” they wrote in their report, released in June.

Information from California’s Employment Development Department appears, at first, to back up their conclusion, showing the unemployment rate for those 16 and over, both female and male, increased between June 2023 and June 2024.

In June 2023, just over 10 million men over the age of 16 were employed in the Golden State. A year later, says the state’s Employment Development Department, the employed in this group dropped by 139,000, to 9,921,000, making for 5.2% unemployment rate in this segment, up from 4.6% a year earlier.

Unemployed women over the age of 16 also increased, from 351,000 in June 2023 to 404,000 a year later, increasing the unemployment rate for this demographic from 4 to 4.6%. The Department’s information also showed that the number of women employed in this group increased, from 8.3 million to 8.44 million.

Asked to clarify their numbers, the Department replied to SD METRO with an email from Samantha Leos:

“There is no published data for persons between the ages of 16 and 20,” she wrote. “It is best to keep in mind that not everyone in the state’s population is part of the labor force.

“Women 16 years and over refers to all women aged 16 year and over. The same applies to women 20 and over. The higher age limit allows for more accurate estimates by filtering out age groups to which the measure doesn’t apply,” she added.

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, part of the U.S. Department of Labor, shows that between June 2023 and June 2024, there were more than 1,000 fewer workers in California’s limited-service restaurants, described as restaurants where guests order, pay and pick up their food from a checkout counter, down to 744,700 from 745,800. It doesn’t break out workers by age groups.

As for why employment at these establishments hasn’t dropped further, due to the increased minimum wage, University of California at San Diego’s Economics Professor Marc Muendler offered this perspective.

“If you go to a restaurant, you want to be treated nicely,” he said. “Therefore, I think the wage is not that sensitive to other market forces.”

Thornberg and Kodaverdian say teen unemployment nearly doubled in two years.

Using numbers from the U.S. Census Bureau, they showed the unemployment rate for California teenagers, those between the ages of 16 – 19, jumped from 10.3% in 2022 to 19% two years later.

The new minimum wage in fast-food restaurants, which increased to $20 an hour from $16 on April 1st this year, impacts teenagers in multiple ways, Thornberg says.

“They desperately need to know how to work,” he said. “You’ll see some of the quotes (in the report) where (people) kind of give a nod to the fact that, yeah, teenagers (because of the higher minimum wage) lose jobs, but who cares?

“I find that to be shockingly short-sighted because there is so much research that shows an early job is a critical component of lifetime success. To deny these kids these opportunities is bad for the state. It’s bad for the efforts to reduce inequality and increasing equity,” Thornberg added.

Nonworking teens, he warns, aren’t learning valuable lessons.

“They don’t understand what it means to be where you need to be when you need to be there, to put your nose down to get it done,” he said. “They don’t understand the function of teamwork because they’ve never had a true teamwork work environment.”

Sarah Archer, a San Diego-based marriage and family therapist, who counsels adolescents, agrees that summer jobs provide teenagers with many a life lesson.

“It builds mastery of a skill, self-efficacy, grit, learning to do hard things, learning to communicate with any age, any person, and provides added self-esteem,” she said. “It also keeps teenagers off their phone and exposes them to different people, whether it’s by race, ethnicity, gender, socioeconomic status and, along the way, building empathy for everyone.”

The New Wage Effect

As one proprietor of a cluster of California fast-food restaurants sees it, the increased hourly wage puts employees in a new perspective.

“At $20 an hour, you look at your employees, and if there was that one you were thinking is marginal, you might recruit somebody to replace that person,” said Tom Trujillo, who, with his family, owns seven Wienerschnitzels, a fast-food hot dog restaurant started in Los Angeles’s Wilmington section on the Pacific Coast Highway in 1961. “The one that might’ve been just getting by at $17.50 or $18 an hour, they were okay but now I think I can do better recruiting and, maybe, move on.”

Of course, employers can’t just fire someone because they’re not worth the new wage, he explained.

“The laws are tough on that, but some of the people who haven’t been as good, they’re getting less hours,” he said. “They might be taking home less money at $20 an hour than they were at $17.”

Trujillo has also cut overtime and reduced the hours at some of his stores, including cutting out breakfast or closing the dining rooms at some locations early.

As for recruiting teenagers, Trujillo said, “We don’t have a lot of entry-level jobs for teenagers.

“Fast food is a grimy business, and if they can work at the mall or at Old Navy or Gap, in an air-conditioned building, they’re doing that,” he added.

His recruiting efforts, which include placing banners on the roofs of his restaurants, have prompted his employees to question why he seeks new people.

“Because $20 an hour is a lot of money. At $20 an hour, everyone better step up,” he said.

The new minimum wage, and the subsequent price increases he’s put through to pay for it, reduced transactions by 7%, resulting in revenue being down between 2 to 3%, so far, this year.

As for how customers are reacting to the increased prices, he says, “It’s a shrug, like, ‘Hey, we know. It’s the same at McDonald’s and Wendy’s and every place else.’”

SD METRO reached out to the corporate headquarters of a number of fast-food restaurants, including McDonald’s, Burger King, Chick fil-A, Popeye’s, Kentucky Fried Chicken, Taco Bell, Wendy’s and In-N-Out Burger, inquiring how the increased fast-food minimum wage impacted their operations and bottom line.

Only one responded.

“I can confirm that on April 1st, we raised prices in (our) California restaurants to accompany a raise given to the Associates at those locations on the same day,” In-N-Out Burger Chief Operating Officer Denny Warnick said in a statement emailed to SD METRO.

New Opportunities

With the new minimum wage, Downey, Calif.-based Navia Robotics is seeing an uptick in the number of inquiries it receives from restaurant owners and operators for its products.

Its robots can handle a variety of tasks, including escorting customers to their table, returning dishes to be washed and bringing them to staging areas so a server doesn’t have to bring them out from the kitchen.

“As far as inquiries go, we have definitely seen an increase,” said the company’s chief technology officer, Peter Kim.

But culture sometimes prevents restaurant owners from adopting them.

“The United States is one of the few countries that has gratuities for food service workers,” he said. “That’s one of the concerns a lot of restaurant workers have when it comes to adopting robots compared to other countries.

“They’re worried their income is going to be impacted by these robots,” Kim added.

As for fast-food franchise owners looking to add robots, Kim says they’ve spoken with some but there’s a hold up.

“The decision-making is done at the corporate level,” he said.

UCSD Economics Professor Muendler views the fast-food industry this way, saying, “If you go to a restaurant, you don’t want a robot. There’s no easy way to make restaurant workers more productive and more efficient.”

Another issue restaurant owners face is managing their youngest workers.

“They don’t show up; they don’t call in sick,” Kim said. “There’s a huge issue finding reliable workers, so the robots are a huge draw for restaurant owners.”

But sometimes the unexpected occurs with his robots on trial.

“After a week or two, sometimes, the restaurant owner calls, saying, ‘We’re not interested in moving forward.’ When asked why, they say that during the trial their human workers started working harder – because they’re worried about being replaced.”

Anxiety & The Phone

The number one worry for today’s teenagers is uncertainty.

“The mobile phone gives knowledge-thirsty teens immediate relief,” said Sarah Archer, a mom and a San Diego licensed family therapist who counsels adolescents. “If you want to know what your friends are doing, you know – by checking your phone.

“If you want to know what Bora Bora’s hotels look like, you can find out – instantly – by checking your phone,” she continued.

As relieving as it is to find immediate answers via that cell phone, it comes with a price.

“The number one trigger for anxiety among teenagers is uncertainty,” she said.

Teenagers, Archer says, have what she calls “low distress tolerance skills.”

“We teach what’s called ‘Dialectical Behavioral Therapy,’” said Archer. “At the core it is teaching emotion regulation, interpersonal skills, mindfulness and distress tolerance.”

Because of that phone, teenagers, she says, don’t even know what it’s like to wait in line without being able to read something.

“There’s a lack of situations to build that muscle,” she said.

One way to combat this, she says, is through a summer job.

“I think a good, old manual labor job – while it might not help a college application – is going to have a bigger impact on a teen’s ability to do hard things in life and stick them out,” she said. “Parents should tell their teenagers to go mow a bunch of lawns, scoop ice cream for seven hours on their feet – not just work at a startup over the summer.”

It isn’t easy to get the kids off the phone, Archer warns, which often comes with a grip and comfort, too.

“A job that gets kids out of that bubble, where they have to put down the phone, because they’re working with customers, doing some kind of manual labor or something that requires using their brains or their hands is a big help,” she said. “At first, it’s awkward not to be constantly checking their phone and they hate it.”

But, in time, there’s change.

“Eventually, it’s a relief for them to be off their phone. It comes with a lot of kicking and screaming but once they’re off the phone, they’re off,” Archer continued.