The Golden State burn: Climate’s impact on homeowners and their wealth

California burns, with more than 3,300 wildfires and 150,000 acres charred so far this year, Cal Fire reports, while 1,100 plus tornadoes, says AccuWeather, tore up the landscape from the Central Plains to the Midwest, the Ohio and Mississippi Valleys, plus one – for the first time in 20 years – in Alaska.

Along the country’s 3,700-mile eastern seaboard, which includes communities from South Padre Island, Texas, up to Lubec, Maine, meteorologists forecast many destructive events this year: Nearly 33 million homes risk wind damage at the cost of $10.8 billion in what could be one of the country’s stormiest hurricane seasons.

About 8 million of them, reports Irvine, Calif.-based CoreLogic, are threatened by storm surge, ocean water thrust ashore by powerful typhoon winds.

The forecast, from a variety of weather services, including the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, is that this will be an “above normal” year, with eight to 16 hurricanes, and four to eight of them being “major hurricanes,” meaning they’ll likely have wind speeds of least 110 mph, perhaps faster.

In fact, Texas’s Gulf Coast already experienced one – Beryl – which came ashore the Monday after this year’s July 4th holiday as a Category 1 hurricane with top sustained wind speeds as high as 80 mph. Insurance losses from Beryl are expected to be between $750 million to $1.2 billion, Artemis reported.

AccuWeather estimated damage and economic losses higher – between $28 to $32 billion. Most of the damage was in rural areas, early reports said.

As for California’s wildfires, there could be some good news.

“Most of California had near to above normal rainfall this year,” said Matthew Shameson, a Riverside, Calif.-based meteorologist with the U.S. Forest Service. “And normally during wet years, we have below normal significant fires.

“We get about the same number of fires, but the significant ones go down,” he added.

CalFire, however, warns that due to new vegetation growth, “dryness may increase … potentially leading to more small fires, with the chance of larger fires depending on wind conditions.

“While there are no immediate signs of drought or dryness, this could change as temperatures rise and conditions dry out,” the organization said in a statement.

“Tornado Alley,” consisting of a line of states from South Dakota down to Nebraska, Kansas, Oklahoma and parts of Texas, once saw many tornadoes. But they’re no longer the epicenter. Twisters are moving east and are just as likely to strike portions of the Midwest and Southeast.

“People just need to realize that tornadoes can occur outside of these areas, and although the area has shifted in the last 35 years from the Plains to the Southeast, it may shift again,” said AccuWeather Meteorologist Jesse Ferrell in a story posted on the forecaster’s website.

The forecaster also warns that tornadoes can happen anywhere, including California.

The National Weather Service says about 800 tornadoes strike each year, killing about 80 people.

But AccuWeather Meteorologist Paul Pastelok says the annual number of tornadoes is closer to 1,400. In the 21st century, so far, 2004 and 2011 hold the record for the most tornadoes, 1,817 and 1,700, respectively.

While it remains early in the year for tropical storms, hurricanes, tornadoes, hailstorms, thunderstorms, and wildfires, these events – even the threat of them – could make for lasting consequences for homeowners, especially their wealth.

Homeowner risk

The U.S. Treasury Department’s Office of Financial Research said in a December 2023 report, “it is becoming increasingly challenging for real estate owners … and related parties to protect themselves from the financial impact of adverse weather events via insurance.”

The risk isn’t limited to just an owner experiencing a decline in their property’s value due to a storm or wildfire or the risk of one.

Also at stake is the impact on banks and other real estate lenders because properties with a reduced value also suffer diminished loan collateral value – or fair market value – which is often used to secure a mortgage. In other words, the property could be underwater, a situation where the property’s value is less than its mortgage.

In addition, the report says, state and municipal governments could see a decline in the taxes they receive from homeowners because their properties are worth less than they were previously due to being either caught up a climate event or located in an area that’s at risk of being hit with floods, hurricanes, severe thunder and hailstorms, tornados, wildfires or tropical storms.

In another report, from February, the U.S. Treasury’s Office of Financial Research estimated houses could lose 6.1% of value and 61% of home equity due to expected losses from a climate event – even the threat of one.

“Climate shocks may devalue real estate, increasing the default risk on mortgage loans and mortgage-backed securities,” the report said. “However elevated default risk does not require the occurrence of an adverse climate event.

“Growing concerns about future climate episodes may devalue home prices today, wiping out homeowner equity and raising default likelihoods,” the report added.

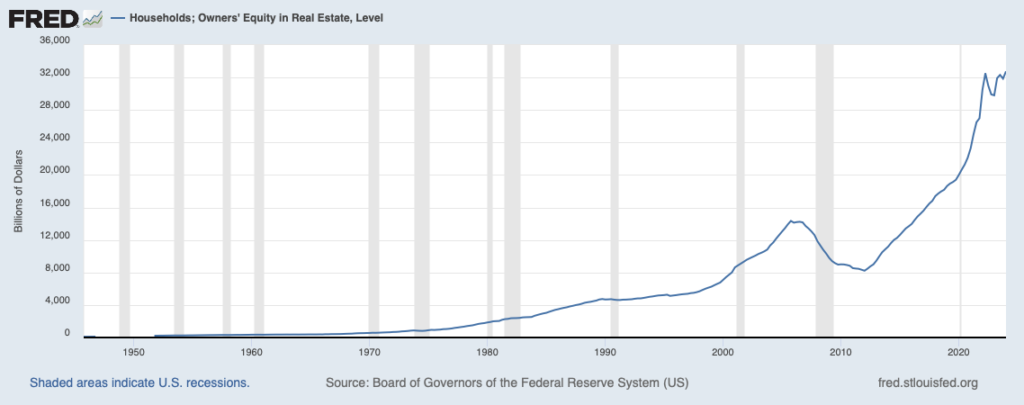

The Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis reports homeowners in the United States, as a whole, have nearly $33 trillion in equity in their homes as of the year’s first quarter.

According to a Pew Research Center report from 2021, homeowners in the United States derive 45% of their wealth from the equity of their primary residence.

The conundrum

As one researcher sees it, towns and cities, which rely on property taxes to fund a variety of services, including schools, police and fire departments, face a dilemma.

“Local governments rely on property taxes, whether that’s from existing properties or the development of new ones,” said Urban Institute Senior Researcher Andrew Rumbach. “There are development dollars that come when you build a new place. And then you’ve got these climate hazards.

“It’s a vicious cycle because there’s a lot of considerations besides climate when we make housing (zoning) decisions. It’s very easy to push off concerns about the long-term risk in favor of the short-term benefits of more developments in hazard-prone areas,” he added.

Plus, he said, “It’s very difficult to get around these issues when a lot of local government folks want to be re-elected.”

Adding to the pressure to rebuild, especially in areas that suffered a climate event, is competition.

“There’s always a nearby town that may be willing to allow that development if the other town doesn’t,” Rumbach said. “And they’re going to get the jobs, the houses and the tax revenue. So, the local government doesn’t exist in a vacuum.

“In some ways, it’s a race to the bottom to see who will allow development in risk-prone areas,” he added.

A recent U.S. Census Bureau report shows recent population growth in some areas of the United States most vulnerable to hurricanes and tropical storms, starting on the Atlantic Ocean coastline in North Carolina down to Florida’s Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico shorelines, around to Texas, including some counties in Alabama, Mississippi and Louisiana.

It also shows population growth in some counties on the Atlantic coastline between Virginia and Maine. In comparison, the graph shows, there’s been a decrease in California’s population along the Pacific Ocean.

One insurance executive, requesting anonymity, framed the issue this way: “If you derive your revenue in your state or town in a coastal area, you absolutely want expensive housing in that dangerous area.”

SD METRO last year reported on a similar development in California, reporting that 4.4 million homes were built in the Golden State’s Wildland Urban Interface, an area where housing and human development interact with undeveloped land and vegetative fuels, which can increase the chances of a wildfire.

The University of California Los Angeles, the story reported, in a study, said much of the growth is due to the state’s Proposition 13, which passed in 1978, which restricts the annual increase on property taxes, resulting in local governments allowing more homes to be built to boost tax revenue.

How does San Diego see the issue of property taxes and development? SD METRO sought out Mayor Todd Gloria for an answer.

“The property tax rolls are not a consideration in our land-use planning,” Mayor Gloria told SD METRO. “San Diego needs housing, and we are looking to maximize housing in developed areas with access to public transit, some of which is near the coast.

“The City is concurrently anticipating the impacts of climate change and has extensive climate resiliency planning to protect infrastructure and property,” the mayor added.

As for how housing impacts property tax revenues of California’s municipal governments, SD METRO’s calls to the California Society of Municipal Finance Officers seeking comment were not immediately returned.

Insurance Issues

With the exception of California, which is experiencing insurance coverage problems due to wildfire threats and state government regulated annual premium increases, elsewhere around the country, where there’s development, there’s an insurance company willing to write a policy – no matter where it’s located.

“As an industry, we don’t view any region as uninsurable,” said Karen Collins, a spokesperson with the American Property Casualty Insurance Association, a Washington-based industry group consisting of home, automobile and business insurers.

But there’s a result, she points out: Annual premiums are increasing.

“The risk on the ground is what the insurance prices are going to reflect,” she said. “And as we (the insurance industry) have more losses, insurance prices have to reflect those costs.

“Our industry has seen a significant increase in premiums to try to realign with what this loss exposure has been in recent years, and that’s becoming a wake-up call to all who are impacted,” she added.

Jimi Grande, a spokesman for the National Association of Mutual Insurance Companies, an Indianapolis-based association representing about 1,400 mutual insurance companies, concurs.

“Nothing is uninsurable,” he said. “There’s always a price for a risk, but if the risk goes up, the cost to insure it goes up.”

The industry is also seeing increased costs for repairing damaged properties.

“Building materials and labor are up by about 38% for each one,” Collins said.

The cost of reinsurance – insurance for the insurance industry — also jumped. According to the Guy Carpenter On Line Index, reinsurance costs spiked more than 100% from 2017 to 2023 and increased again by just over 1% between 2023 and 2024, which is causing insurance premiums to increase, too.

Nancy Watkins, a consultant to the insurance industry in Milliman’s San Francisco office, says increasing annual premium costs can cause consumer problems.

“I think people understand that if they have an insurance policy, they are transferring risk,” she said. “What doesn’t make sense is the assumption that they’re entitled to an insurance policy at a price they’re able to afford or that is very closely related to the price they assumed it would be when they bought the property – or both.”

Land-use policies

Collins says where housing is zoned and developed needs to be reviewed.

“There’s not going to be a sudden stop in development,” she said. “But we need to be smarter about how we approach this, making sure we include mitigation and consideration for the risks of the area that we are building in.”

“As a country, we’ve never taken land use as seriously as we should have, which, historically, has put the insurance industry and some environmental groups in the same pool together, where they’d say, ‘Hey, Mother Nature put that grassland around the coast for a reason. It’s like a sponge when storms come in. If you build houses there, the safety spot is gone. It’s a bad spot to develop,” Grande said.

“But now we’ve developed them and then we (the insurance industry) undercharged, and now the weather’s getting worse, and so what are you going to do? Take the entire community and move it?” he added.

Page can be reached at dpage@sandiegometro.com