By Luke Nichter

Most of us observe politics from the cheap seats – a kind of kabuki theatre that does not really tell us how it actually works behind the scenes. Preconceived ideas and political commitments exaggerate our blind spots. The more white-hot the political moment, the worse our judgment gets. Instead, we must remember that much of what happens in Washington happens not for policy reasons or partisan motivations, but for selfish, personal ones. If it is true that politics makes strange bedfellows, it is especially true when it comes to the crafting of political legacies.

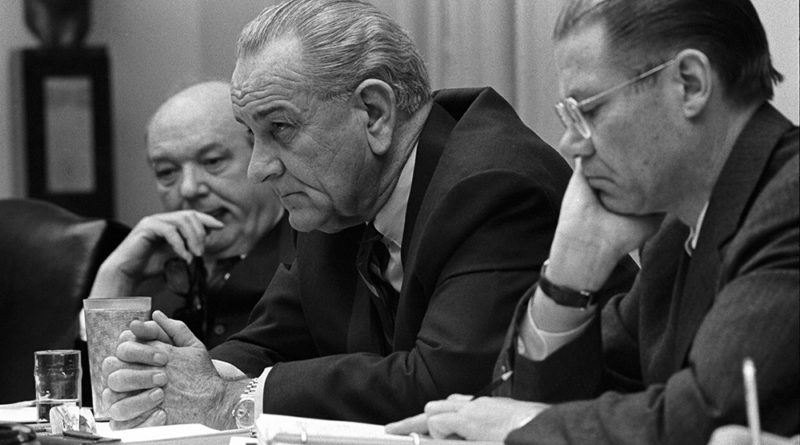

Consider the precarious political position of Joe Biden after his recent disastrous performances that have inspired calls for his withdrawal from the presidential race. History can be a useful guide. In the run-up to the 1968 presidential election, Lyndon Johnson was under pressure from the left wing of his party, primary challengers and the media to not run for re-election amid the war in Vietnam. Johnson had been the hardest-working Senate majority leader in modern American history, and brought that same work ethic to the White House where he worked to complete not only John F. Kennedy’s unfinished legacy but also that of his mentor, Franklin D. Roosevelt. Yet LBJ was never fully embraced as president by his own party and America’s war in Vietnam distracted from his domestic successes with the Great Society. Johnson faced a difficult choice as the 1968 election neared. It is a story I tell in my book, The Year That Broke Politics: Chaos and Collusion in the Presidential Election of 1968.

The questions Johnson faced were strikingly similar to the ones Biden now faces. How does a president withdraw from an election? What precedent is there? What process is used to make such a decision? What considerations are there for the nation – political, economic, national security – and, for the president, in terms of personal or legacy concerns?

‘Well, what do you think? What shall I do?’ LBJ asked Lady Bird Johnson the day of his last State of the Union address. It was 17 January 1968. That evening he would deliver the least hopeful and most defensive of his annual messages to Congress. The question going over and over in his mind was whether he should use the occasion to announce that he would not run again. Up until the moment he delivered the speech, those closest to him were not sure what he was going to do.

Even as he gave his State of the Union address, Johnson had a secret. In his jacket pocket, he carried a piece of paper that contained an alternate ending: ‘Accordingly, I shall not seek and I will not accept the nomination of my party for another term as your President.’ Having these words on a separate piece of paper would allow him to maintain the element of surprise since the ending was not part of the prepared text given to the press in advance. Johnson was free to pull out the piece of paper and use the statement whenever the moment felt right.

Leading up to the State of the Union, Johnson shared his intentions with only a close inner circle, including his wife Lady Bird and outgoing governor of Texas, John Connally, who had come to Washington in 1937 as one of LBJ’s first staffers after Johnson won a special election to Congress. The first lady, Johnson’s underappreciated strategist, was perhaps the only person in Washington who really knew what he was thinking. She judged the withdrawal statement beautifully written. ‘Lyndon handed me a piece of paper, a letter from John Connally with his recommendations that he go with the statement tonight,’ she wrote in her diary, ‘because he would never have a bigger audience… the occasion of the State of the Union was a noble time to make an announcement. Lyndon had to weigh this against the fact that the whole 1968 program of action would thereby be diluted, if not completely ignored.’

However, Johnson could not go through with it. He delivered his State of the Union address without the alternate ending. Some aides were surprised since it had been discussed with his speechwriters in advance, but the timing did not feel right to LBJ.

What goes through a president’s mind at a time like that? How do you know when it’s the right time to step down? How do you do so in a way that does not seem like a response to the media, your critics, and those who would prefer you let someone run who is younger or more in tune with the future of the party? How do you do it on your terms, with your head held high? It is a difficult needle to thread; otherwise, stepping down in response to critics’ signals they must have been correct.

In contemplating withdrawal, Joe Biden is not defending a single debate performance or even a four-year term. The stakes are much higher for him than we might realise. He is defending half a century in political life that goes back to his first election to the Senate in 1972. He will not allow this final chapter to define his entire career.

No matter how many critics Biden has, the American people elected him for a full term of office. No president wants to be a lame duck a moment earlier than necessary. Biden feels he has a duty to defend the presidency and carry out the agenda he was given the mandate to fulfil. Short of impeachment and removal from office, no one can take that away from him unless he voluntarily withdraws.

LBJ ultimately withdrew at the end of a nationally televised address on the Vietnam War on 31 March 1968. Johnson said he would not ‘devote an hour or a day of my time’ to anything other than his duties as president and he would not accept the Democratic Party’s nomination again. He publicly supported his vice president, Hubert Humphrey, as his successor.

Johnson had asked aides to study how Harry Truman withdrew from a run for re-election on 29 March 1952, when Truman was hesitant to face a strong opponent, General Dwight Eisenhower. Biden, born in 1942, is old enough to remember those two precedents. It might even have been a reason why the date of his 2024 State of the Union was fixed so late in the calendar to March. From a historical standpoint, March was the month to watch – and it came and went without fanfare.

We now know that Johnson’s health played a more prominent role in his decision to disengage in 1968. He was 59 at the time and would reach the age of 60 – the same as his father, who died prematurely following an earlier stroke – on 27 August, the day the Democrats planned to nominate their presidential candidate. It was no coincidence that the date was the same as LBJ’s birthday. Four years before, in 1964, he had been nominated on his birthday at the convention in Atlantic City.

Lady Bird might have been the only one who knew his true thinking. Her diary reveals LBJ’s preoccupation with his health, but there was also another reason he thought it might be time to step down. ‘I think what was uppermost – what was going over and over in Lyndon’s mind,’ she wrote in her diary, ‘was what I’ve heard him say increasingly these last months: “I do not believe I can unite this country.’” She saw the strain he was under from ‘the growing virus of the riots, the rising list of Vietnam casualties, criticism from your own friends, or former friends, in Congress’ and noted that ‘most of the complaining is coming from Democrats.’

First Lady Jill Biden might now be the only one who really knows her husband’s thinking. If Biden withdraws he will, briefly, be a hero to his party and the nation. In 1968, LBJ’s act of self-sacrifice was seen as virtuous and about putting the country ahead of his political future. As with Johnson, a withdrawal from the ballot is not necessarily a withdrawal from politics. LBJ simply shifted his political energies from the ballot to focus on the war in Vietnam and influencing the choice of his successor.

Following a president’s withdrawal, however, the excitement shifts to the challengers. Alternative candidates – governors and senators – will emerge. Biden will immediately endure defections – from his Cabinet and staffers who flock to others out of a desire to work in the next administration. In 1968, the Democrats were divided over the Vietnam War, and prominent candidates like senators Eugene McCarthy and Robert Kennedy challenged the establishment.

This year, divisions over Israel threaten to splinter the party further, although Biden has had no serious primary challenger. Millions watched the chaos of the Democratic National Convention in Chicago on television from their sitting rooms in 1968. The violence in the streets outside the International Amphitheater, which Mayor Richard Daley’s police joined in, spelt doom for the Democrats. Richard Nixon campaigned on the platform of ‘law and order’ in contrast to the chaos facing his opponents. In 2024 the Democrats are headed back to Chicago for what has the potential to be a very lively convention.

Biden’s replacement will be defined from the outset by their distance from the incumbent but they will never quite be able to escape that shadow. As the Democratic nominee, Hubert Humphrey learned in 1968, it is very difficult to quickly organise a campaign around a meaningful theme, balancing between presenting both continuity and change, under such conditions. Like Vice President Kamala Harris, Humphrey was not the strongest candidate but rather the one who could most easily be inserted into what was left of Johnson’s campaign infrastructure. Another option in 1968, such as Eugene McCarthy on the left, or a John Connally on the right, each representing one half of the New Deal coalition of northern liberals and southern conservatives, might have caused lasting division in the party – a serious danger, especially in a year that favoured the Republican candidate.

If Biden’s primary concern is his own legacy, there is another role that he could play in the election, however. As I explore in my book, the more that LBJ was pressured to not run, the more he found common ground with his long-time political nemesis, Richard Nixon. Despite his notional party loyalties, Johnson quietly supported Nixon’s election over his vice president, Hubert Humphrey. They were each the best of their generation on their side of the aisle, but, when not facing each other on the ballot, Johnson and Nixon came to realise they needed each other. It was not so much what they had in common that led LBJ to support his successor’s election, but that they had so many of the same critics.

Whatever Biden decides, he has examples to guide him, with LBJ’s decision in 1968 being the best in recent history. For now, the real question is whether he has a piece of paper at the ready in his pocket.

Editor’s Note: This column originally appeared in Engelsberg Ideas (engelsbergideas.com)

Engelsberg Ideas is home to great writing from leading thinkers on history, culture and geopolitics, featuring essays, notebooks, reviews, and historical portraits as well as regular podcasts.

Luke A. Nichter is a Professor of History and James H. Cavanaugh Endowed Chair in Presidential Studies at Chapman University. He is the New York Times bestselling author of eight books including, most recently, The Year That Broke Politics: Collusion and Chaos in the Presidential Election of 1968 (Yale University Press, 2023), which was chosen as a Best Book of 2023 by the Wall Street Journal. He is now at work on a book tentatively titled LBJ: The White House Years of Lyndon Johnson.

Luke Nichter interviewed with SD METRO late last year about the 1968 election. That interview can be found

here.