Pinnacle’s Price: Women and Professional Success

Despite one barrier after another being kicked aside so women can advance in their careers, it seems there’s a mystery: What do they experience and sacrifice at work, especially as they climb the company’s ranks, enter the C-suite, and become the CEO?

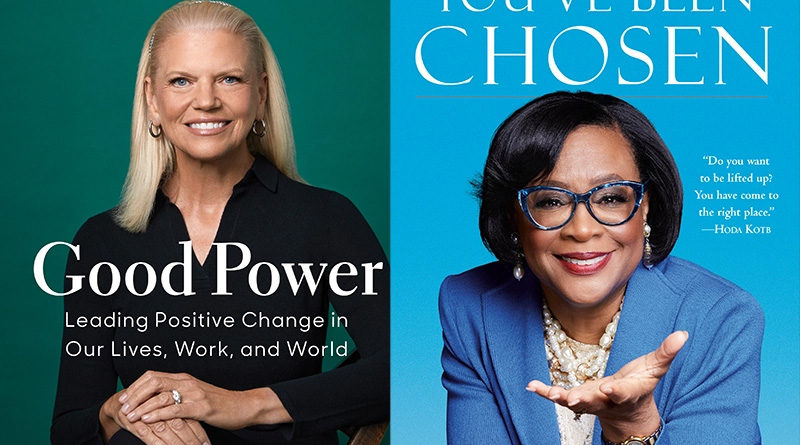

Former IBM CEO Ginni Rometty, the first woman to hold the job at Big Blue, and current NBA Dallas Mavericks CEO Cynt Marshall reveal some of what they endured during their careers in their books, but Marshall goes farther, describing the insults and objections.

“Nothing about being a woman in a male-dominated industry, or a Black person in a business dominated by white executives, is easy,” she writes in You’ve Been Chosen: Thriving Through the Unexpected. “I’ve dealt with people who think I’m fundamentally not as smart as them, not as talented as them, or not as worthy as them.

“There were people who couldn’t believe that a woman – let alone a Black woman – was capable of being an effective, powerful executive. With every promotion, someone in my circle assumed I would fail,” she adds.

Could it be worse?

It was, especially after AT&T’s board of directors selected Marshall to be a corporate officer.

With the promotion, her boss offered plenty of unsolicited advice, telling her to cut her hair; wear more white clothes because they would “complement” her skin color; use her full first name, Cynthia; lower the volume of her voice; and stop using the word “blessed” because it was “’too churchy.’”

How did she respond?

She turned down the promotion, with her boss saying, “’I agree with your decision … You’re smart, but you don’t have what it takes for this.’”

The boss’s ethnicity isn’t revealed, but the gender is: It was a woman.

The CEO, however, wasn’t taking “no” for an answer.

“’We selected you to be an officer just the way you are now, Cynt,” AT&T CEO Ed Whitacre told Marshall. “You’re the person who’s getting everything done. I don’t want you to change a thing. So let’s start over.’”

With those words, she reversed her decision.

One expert on what women experience at the office says Marshall’s story is similar to her findings.

“What has surprised me is that, especially in financial services and technology (industries), we hear more challenging stories (from women),” Deepa Purushothaman told SD Metro Magazine. A former Deloitte partner and author of a book, she’s also researched and written about women’s professional experiences for the Harvard Business Review (HBR).

While she doesn’t have enough data to suggest it’s completely accurate, there are enough examples, she says, showing women have a more challenging time with a boss who’s a woman.

“The women who’ve come before have had to conform, have had to sacrifice to get to the (boss’s) seat, so there’s an expectation everyone behind them will do the same,” Purushothaman said. “So sometimes women are harder on other women.”

She noted that she and others she’s worked with have interviewed more than 2,000 women in professional and corporate ranks about their careers and challenges. Why is this important? The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics shows in a 2021 study that women make up nearly 52% of those in management, professional and related occupations.

Even after a highly successful, 30-plus-year career with AT&T, with the last years as one of its most senior executives at their Dallas headquarters, Marshall took flak upon joining the Mavericks.

“When I got to my current job as CEO of the Dallas Mavericks, there was a person there who openly said, ‘Don’t listen to her. She won’t last ninety days,’” she writes.

Mavericks owner Mark Cuban recruited her while the team was “reeling from a #MeToo scandal … centered around a toxic work culture for women,” Worth magazine reported.

Rometty faced her own challenges, but her career, compared to Marshall’s, seems almost gilded. Rarely does a reader come away from her book, Good Power: Leading Positive Change in Our Lives, Work and World, thinking she was insulted or riddled with self-doubt.

According to one published report, written by Purushothaman and two others, Lisen Stromberg and Lisa Kaplowitz, that might not have been what she experienced.

“Study after study has revealed that women are viewed by both men and other women as having lower leadership potential and being less competent than men with similar skills and backgrounds,” they wrote in an article published in HBR. “Given the bias against them, the women we interviewed felt they had to be ‘perfect’ to reach their seats.”

Rometty backs that up, writing, “Preparation helped protect me, at least in my own mind, from gender bias, conscious or otherwise. Was it fair? No. But I was and remain a product of the times in which women have to work extra hard to prove themselves – thirty years later this is still true in so many places, including the tech industry as a whole and the ranks of senior management across the board.”

Minority women, the three authors write, come under even more pressure.

The research “revealed that this tendency toward perfectionism presents more severely for women of color (WOC), who have been told – and who have internalized – that they need to work twice as hard,” the authors wrote. “As the ‘only’ in the room, many women, and particularly WOC, believe their success or failure will serve as a generalization for the success or failure of their entire cohort.”

After graduating from Northwestern University with a bachelor’s degree in computer science, Rometty joined General Motors as a junior programmer in the Chevrolet Information Systems division. After realizing she wasn’t a car aficionado, she joined IBM in Detroit as an assistant systems engineer in 1981.

Rometty details her hazards and victories, including the acquisition of Pricewaterhouse Coopers consulting unit for $3.5 billion while leading one of the IBM’s largest business units, the Global Services Americas division.

Like Marshall, she had her fair share of challenges and, at one point, describes breaking down emotionally because the stress was nearly unbearable. But she also puts a positive spin on what she faced and defines how she used power to benefit her many colleagues.

As for what happens when women reach their company’s upper echelons, Purushothaman says many undergo a watershed moment.

“Most of them will find themselves in a crisis. And some of it’s an identity crisis, some of it’s a health crisis and then they start to question, is this worth it?” she said.

Purushothaman’s findings shouldn’t be dismissed, but Marshall and Rometty show there are many stories – not one narrative – about how women view their accomplishments. Marshall and Rometty tell engaging stories about the price they paid to reach the top, but Marshall’s is the richer autobiography.

Douglas Page can be reached at dpage@sandiegometro.com.