The Fearless Shirley Weber

Assemblywoman Shirley Weber in conversation. (Photo by Evan Lewis for CALmatters)

Chased out of Arkansas as a child,

Shirley Weber

won’t back down in California Capitol

By Jessica Calefati | CALmatters

HOPE, Ark. — When Shirley Weber and her siblings fled this place as children in 1951 on a midnight train bound for California, their destination seemed so distant and unfamiliar to the relatives who stayed behind that they called the state a foreign land.

_____________

As Weber stood at the edge of her family’s 100-acre farm on a recent visit, her first in decades, memories of her birthplace came flooding back. She and her cousins swapped stories about shelling peas on her aunt’s screened-in porch, how dark it got at night before the city installed street lights, and what forced her family to flee — her sharecropper father’s refusal to back down during a dispute with a white farmer, and the lynch mob that threatened to take his life.

Weber inherited that tenacity from him, along with his belief that education is the portal to a better life. She rose from her hardscrabble roots to earn a Ph.D. and become an academic, a school board member and now a legislator, always championing the causes of underdogs.

Inside the California Capitol, she’s an education reformer who doesn’t flinch when taking on the powerful teachers union, shrugs off setbacks, and “just won’t die” on the issues she cares about.

“I don’t fear that I’m going to get lynched at night or that someone is going to bomb my house. I don’t fear that,” Weber said. “What my predecessors stood for and fought for was a whole lot harder than what I’m fighting for today.”

At age 68, the Democratic Assembly member from San Diego, a tall black woman whose short Afro is speckled with gray hairs, has a 40-year career as a university professor behind her and little ambition for higher office.

“She doesn’t need this job, and that’s freeing,” said Sen. Toni Atkins, a fellow San Diego Democrat who considers her a mentor.

Weber insists that the state “can and must” do a better job teaching low-income students, and has devoted herself to the cause. California’s achievement gap between poor kids and their wealthier peers hasn’t budged in decades, and the state’s needy fourth graders now rank dead last in math compared to other states.

Her solutions include tightening the requirements for teacher tenure and mandating greater fiscal accountability — ideas that make her the rare Democrat at odds with the California Teachers Association, the state’s largest union for educators.

Often, her proposals stall in the Democratic-controlled Legislature or get vetoed by fellow Democrat Gov. Jerry Brown. Critics consider her a stubborn, impatient, anti-teacher’s union zealot. But Weber says she’s not deterred.

“It doesn’t bother me that I’m upsetting people who don’t want to change because they’ve got to change,” Weber said. “I come out of a legacy that says, if you don’t keep kicking at the door, you’ll never be able to wear it down or open it. So, I keep kicking.”

Weber’s life as a Californian began at age 3 in South Los Angeles’ Pueblo del Rio housing project, where she and her seven brothers and sisters lived alongside other African American families.

Her father David Nash supported his brood with decent wages earned working a union job at a steel mill. Her mother Mildred was a homemaker. But having only made it to the 6th grade back in Arkansas, Weber’s father was semi-literate. He could write his name, she recalls, and “read a little.”

Black men of his generation who hailed from Hope rarely advanced to high school, she said. White farmers would pressure black sharecroppers to pull their sons from school and have them help work the fields, effectively ending their careers as scholars.

“My father always felt like if he’d had more of an opportunity to go to school, he would have had more choices in life,” Weber said. “Not that he would have been richer or better off. He made decent money. He thought he would have had more choices.”

Knowing what he’d missed out on and wanting better for his children, Nash groomed them to love learning and insisted that they finish high school, which they all did.

Weber did more than just finish.

She graduated atop her high school class and attended UCLA, where she earned bachelor’s, master’s and doctoral degrees in communications with a focus on political movements, all by age 26.

It was at UCLA that she met her husband Daniel Weber, who went on to become a judge and died in 2002 after a long career in law.

She taught college classes at California State University at Los Angeles and Los Angeles City College before joining San Diego State University, where she helped start the Africana studies department and went on to teach for four decades.

Weber says it wasn’t until she had nearly completed her Ph.D. that she first encountered the sort of ugly racism that had held her father back as a child and endangered his life as an adult. As she worked to complete her dissertation on Marcus Garvey, an activist who promoted black nationalism, she said she learned that none of the senior professors in her department were willing to serve on her review committee, a move that could have torpedoed her chances at earning a doctoral degree.

“They told me to go away,” she said, conceding that she’d thought about giving up and abandoning the program. Instead, she recalled, she threatened to seek an injunction against the university and convinced the department to back down.

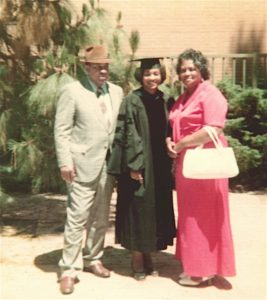

In 1975, when it came time to graduate, Weber said she wanted to skip the ceremony but thought twice about doing so once she realized that it would fall on Father’s Day.

“He loved graduation. He never missed one,” Weber said, calling her father’s record of perfect graduation attendance an incredible feat given the size of her family. “Any time he came to work asking for a half-day off, someone would say, ‘You must have a kid graduating.’ He didn’t skip work for anything else.”

Weber’s first experience as an elected official came in 1988, when she joined the San Diego Unified school board. Her goal: improve the system for her young children, who were seven and 10 at the time.

“You put your kids in the system, you want to make it better,” said Weber, who went on to become board president and served until 1996.

She’s a longtime resident of the Oak Park neighborhood on San Diego’s working class southeast side, and her children attended their neighborhood schools — Encanto Elementary and Gompers Secondary.

Weber’s daughter Akilah, 39, recalls having an “excellent” public school experience that helped launch her into college and later medical school. Today, she’s the city’s only fellowship-trained pediatric gynecologist. And she’s struggling to find a public school suitable for her 5-year-old son.

Gompers had become San Diego’s worst-performing school and was on the verge of a state takeover when it was converted into a charter school in 2005. Gompers Preparatory Academy’s new leadership has slowed the relentless pace of teacher turnover that once plagued it, but is still struggling to boost students’ academic performance.

“We didn’t have this issue when I was a kid,” said Akilah Weber, who lives in her mother’s Assembly district.

Even some lawmakers share Akilah’s frustration and have told Weber privately that they won’t enroll their children in public school because of concerns about quality.

“And yet they sit here and tolerate it,” said Weber, who declined to name any names. “It’s unacceptable.”

California public schools’ need for improvement isn’t in dispute. Less than half of students passed the most recent state test in reading, and only a third passed math. But there’s wide disagreement about the remedies.

The policy solutions Weber thinks would work best frequently get blocked by the California Teachers Association, which sponsored a mandatory kindergarten bill she carried in 2014 but has been her adversary ever since.

The union strongly opposed Assembly Bill 1495, a 2015 Weber proposal that sought to change the way public schools evaluate educators, who can gain lifetime job protections after just 18 months. It was Weber’s response to the Vergara v. California ruling, which found that the state had violated low-income students’ constitutional right to a public education by too often placing them in classrooms with poorly prepared, ineffective teachers.

In a 2015 San Diego Union-Tribune op-ed, she labeled the state’s tenure system “irrefutably broken” and called the ruling, which was reversed on appeal, a “wake-up call for all of us responsible for educating California’s children.”

The union didn’t see it that way.

And when Weber’s Democratic colleagues signaled their plans to comply with the union’s wishes and hold her bill in the Assembly Education Committee, obstructing its path to the Assembly floor, Weber lit into them.

“When I see what’s going on, I’m offended, as a senior member of this committee, who has probably more educational background and experience than all ya’ll put together on top of each other,” she said during the meeting held to vet the proposal, her forceful voice quivering with emotion.

She found Democratic Assemblyman Patrick O’Donnell’s desire to slice off a piece of her bill and make it his own even more galling.

“You’re gonna rape me, rape my bill and take it as your own,” Weber said in a 2015 interview with L.A. Weekly. “After the work we’ve done, without my name on it? I’m not having that. You may do it, but not without my permission.”

O’Donnell, Weber’s frequent foe and a union ally who represents Long Beach and chairs the Assembly Education Committee, declined to comment for this story.

This year, Weber carried another tenure bill that seeks to extend the length of time teachers must work before earning it. AB 1220 cleared the Assembly Education Committee and even the Assembly floor before stalling in the state Senate under pressure from the union. Several weeks ago, when the measure’s fate was uncertain, she choked up at church asking others to pray for her continued strength.

“Shirley Weber is a change agent,” said EdVoice President Bill Lucia, whose charter school advocacy organization frequently sponsors and supports her legislation. “She’s not looking over her shoulder waiting for some signal to be courageous for kids. She’s courageous for kids all the time.”

California Teachers Association spokeswoman Claudia Briggs said the union respects Weber but acknowledges it hasn’t “seen eye-to-eye with her” very often in recent years. Teachers believe they should be able to collectively bargain the standards by which they’re evaluated, and Weber does not, she said.

“Our members want her to listen to them, to listen to the voices of educators,” Briggs said. “They’re the ones who work day in and day out with students. They’re the ones who know what’s best for them.”

The lawmaker’s staff say she’s been trying unsuccessfully for months to schedule a meeting with California Teachers Association President Eric Heins to start that conversation. Briggs said Heins visits Sacramento often and is always willing to meet with lawmakers.

“I’m a difficult person for them to handle because I’m not easily intimidated,” Weber said, speaking about her relationship with the union. “I told them, if my Daddy was threatened by the Klan, my God what the heck am I worried about?”

Gov. Jerry Brown is another familiar adversary for Weber.

Last year, he vetoed her AB 2548, which would have required the state to use a single score to rate public schools, making it easier for parents to compare them. He also vetoed her AB 2826, which would have established a new framework for teacher assessment.

In veto messages, he wrote that AB 2548 was “unnecessary and premature” and that AB 2826 “wouldn’t materially change current teacher evaluations in California.”

Still, Weber says they have a strong relationship.

Brown declined to comment for this story, but in past public remarks he’s made his educational philosophy clear. He believes local leaders are best suited to address problems and that the state should have a very limited role in mandating solutions.

“We don’t agree hardly ever, but Jerry and I are good friends,” Weber said, recalling a time that Brown ignored the seating arrangements at a Capitol dinner so that he could sit next to her and bend her ear. “I’m one of only a few people who will argue with him. He likes that.”

One topic on which Weber and Brown do agree is racial profiling. Two years ago, he signed her controversial AB 953, which requires police departments across the state to collect demographic data on the people they stop.

The two met during his first term as governor in the 1970s, when he worked closely with her husband — who had always bugged her about running for office — and then Assembly Speaker Willie Brown to elevate black lawyers to the bench.

“I never ever thought there was a cap on what the Webers as a team or individually could achieve or accomplish,” Willie Brown said. “They were both God-given, talent-wise.”

Having worked in and represented her corner of San Diego in various capacities for almost 50 years, Weber is well established in the 79th Assembly District and has faced only nominal opposition at the polls since her election. She says she’s been recruited to run next year for state Superintendent of Public Instruction but isn’t interested.

Under California’s term limits, she has a maximum of seven more years in the Assembly.

She’s hoping to accomplish one key goal far sooner: greater transparency and accountability for the extra cash school districts have been receiving since 2013 to help needy students. CALmatters reported on the dearth of available information earlier this year.

Brown has resisted any effort to tinker with the school funding formula that distributes the money, but at a meeting in January with the Legislative Black Caucus, he acknowledged during a conversation with Weber that changes must be made, two other lawmakers in attendance confirmed.

Weber recalled: “I hadn’t said anything in the whole meeting, and he looked at me like, ‘What’s wrong with you?’ and I said, ‘Well, the only thing I want to say is this: You made an agreement with us four years ago about the Local Control Funding Formula. It has not done what it needs to do and you need to fix it before you leave.’”

“And he looked at me and said, ‘Yeah, I know.’ Whether he will or not, I don’t know, but he knows it needs to be fixed.”

CALmatters is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California’s policies and politics.

About the Author

Jessica Calefati CALmatters from The Mercury News, where she worked as a one-woman Sacramento bureau covering politics and state government. She also investigated a Wall Street-traded online schools company that’s reaping millions in state funding while failing thousands of California students. That work got the attention of California Attorney General Kamala Harris, who recently reached a $168.5 million settlement with the company over claims it manipulated attendance records and overstated its students’ success. Before moving to California three years ago to follow Gov. Jerry Brown and the state Legislature, Jessica lived in her native New Jersey and wrote about state education policy and the Newark schools for The Star-Ledger. There she covered New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie’s war with the powerful teachers union, Mark Zuckerberg’s $100 million gift to the Newark schools and a fiery community activist with political pull whose charter school used millions in public money to bolster a real estate fiefdom she controlled. Email: jessica@calmatters.org