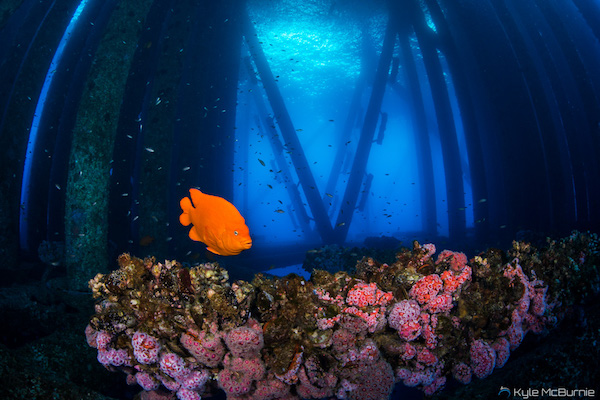

Diving Deep for Conservation

A scuba diver investigates the marine life harbored beneath an oil rig off the coast of California. (Photo: Kyle McBurnie)

Amber Jackson and Emily Callahan Reimagine

The Future of California’s Oil and Gas Rigs

With the Organization Blue Latitudes

By Brittany Hook

The California coast is lined with 27 offshore oil and gas rigs that can be seen jutting out across the horizon — a reminder of humans’ dependence on fossil fuels. Below the surface, however, these platforms are home to some of the most dynamic ecosystems in the world, harboring everything from mussels and scallops to garibaldi and rockfish. As many of these enormous rigs are approaching the end of their viable production lives, scientists, environmental agencies, and oil companies are left begging the question: should the rigs stay or should they go?

Emily Callahan and Amber Jackson, two alumnae of Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California San Diego, have made it their mission to dive below the surface of these oil and gas platforms to determine the best possible “afterlife” scenario for these complex structures.

The two women met in 2013 while taking a scientific diving course at Scripps Oceanography, where both were pursuing Master of Advanced Studies degrees in Marine Biodiversity and Conservation. A conversation soon emerged about Rigs-to-Reefs, which is the name of a state law and associated program that essentially converts decommissioned oil and gas rigs into artificial reefs.

“What you’re focusing on with Rigs-to-Reefs is everything below the surface, like the tip of the iceberg. That’s where all the life is,” said Callahan, a marine biologist and PADI certified divemaster with expertise in environmental consulting.

When she first came to Scripps, Callahan had only recently learned about the success of the Rigs-to-Reefs program in the Gulf of Mexico, where 500-600 decommissioned oil platforms now serve as artificial reefs and provide abundant fishing opportunities, world-class diving and recreational activities, and an ecological hotbed of underwater activity. She was stunned to learn that none of California’s rigs had been approved for a similar Rigs-to-Reefs conversion. Callahan shared her interest in the program with Jackson, who was equally enthralled.

“We really made it our mission in grad school and we’re still working on it — to combine science with powerful imagery and a meaningful message to change the tide of public perception around this program,” said Jackson, a fiery-haired oceanographer with a passion for science communication. “It’s been the cornerstone of what we do and it fuels our exploration and educational initiatives.”

Inspired by the possibilities of Rigs-to-Reefs implementation in California, Callahan and Jackson focused their joint thesis on the topic. Their innovative research led them up and down the coast of California where they dived numerous platforms, conducted ROV surveys, studied the biodiversity of marine life on and around the structures, and analyzed the legislation surrounding Rigs-to-Reefs. They also documented their findings through video, photography, and social media — engaging visual mediums that have enabled them to show the public the beauty and importance of these thriving underwater regions.

Rigs-to-Reefs is a controversial law and program in which an oil company chooses to modify a platform so it can continue to support the valuable and fragile ecosystems that have formed on and around the structures. The decommissioning process still holds platform operators responsible for removing drilling infrastructure and capping and sealing the well — and they remain permanently liable for any damages coming from the well — but the upper portion of the rig (at least 85 feet for ship clearance) is cut and towed to an alternate location or the structure is toppled on its side.

Some environmental groups oppose the Rigs-to-Reefs program because it transfers liability of the structure from the oil companies to the state or the Department of Fish and Wildlife, which then manage it as an artificial reef. The program also saves the oil companies money, upwards of millions of dollars, but any savings are split 50/50 between the company’s stakeholders and the state, which is required to use that money for marine conservation and education — a silver lining according to Callahan and Jackson.

The women also argue that the removal and disposal of such enormous structures —some as tall as the Empire State Building — is costly and comes with a massive carbon footprint. California doesn’t have the infrastructure on land to recycle these structures, so the only viable option for complete removal is to cut the structures down, load them onto gigantic barges, and tow them to Southeast Asia where they can then be broken down and recycled. According to Jackson, the bunker fuel used by barges outside of state waters “makes gasoline look like champagne.”

After examining the Rigs-to-Reefs program from all angles, Callahan and Jackson determined that it would be a beneficial program for the state of California, providing an ecologically and environmentally friendly alternative to complete rig removal.

“The future of conservation is that you’re going to have to work with the government, you have to work with oil companies, you have to work with the ‘bad guys’ if you want to change what they’re doing and make a positive impact for the environment,” said Jackson. “Emily and I are not pro oil and gas development; we’re working on decommissioning the end life stage of these platforms. But I just love the challenge of trying to communicate that there is an ecological, economic, and social benefit to repurposing these structures as reefs — not only in California but around the world.”

Upon graduation from Scripps in 2014, Callahan and Jackson decided to continue working together and co-founded Blue Latitudes, an organization that uses scientific research to form a comprehensive study of the ecological, socio-economic, and advocacy issues surrounding California’s Rigs-to-Reefs law and program. Blue Latitudes provides neutral and scientifically based consulting services to various clients, including gas and oil companies and environmental groups, to assess structures and determine whether they are good candidates for Rigs-to-Reefs.

Blue Latitudes also operates as a non-profit organization through a fiscal partnership with Mission Blue, a global initiative to protect the world’s oceans led by famed oceanographer Sylvia Earle. This wing of the company allows Callahan and Jackson to focus on education and outreach, and the two are currently forging relationships with teachers and schools across San Diego and Los Angeles and developing unique classroom curriculum about marine science for middle and high school students.

The duo continues to spread the word about their research through speaking engagements at aquariums, libraries, classrooms, and more. And they are digitally savvy — constantly updating their social media accounts with stunning images from their latest diving adventures and information about their latest projects. They also educate audiences through a YouTube channel called ScienceSea TV, through their website, and as guest bloggers on National Geographic.

The women credit their Scripps education with providing them the expertise needed to succeed as scientists, explorers, and entrepreneurs.

“Scripps has really given us the right tools to be successful with our business, so that’s been really exciting,” said Callahan, noting that she frequently emails former advisors and Scripps researchers Peter Franks and Jules Jaffe, among others, with questions. “We have such great resources at Scripps to talk to about everything from imaging these platforms, to understanding the biodiversity, to running the ROVs. I’m really grateful to have that support.”

“One thing I think we really took away from our master’s program at Scripps and at the Center for Marine Biodiversity and Conservation was not only understanding the science, but also understanding how to communicate it effectively,” said Jackson.

“Amber and Emily embody a sense of bold environmental activism that seeks to find solutions to environmental problems that are mutually beneficial to industrial goals and those of the environmentalists,” said Jaffe, who served as co-chair on Callahan and Jackson’s thesis advisory panel. “The Rigs-to-Reefs program’s goal is to save industry money, while at the same time having them share the savings with environmental groups. It’s a win-win for the two factions, but an even bigger win for the organisms that have made these underwater offshore oil platforms their homes, as they will, hopefully maintain the deeper parts of these structures.”

The future looks bright for the ladies of Blue Latitudes, and they already have plans to expand their expertise to international waters. They have an expedition planned in March 2017 to Malaysia, where they will explore and assess the country’s platforms. Their long-term goals include researching the oil and gas platforms of Southeast Asia and Australia, all the while following their overarching goal of thinking creatively about the resources that we have and how to preserve the ecosystems thriving quietly below the surface.

“Our general message of Blue Latitudes is to dig a little deeper,” said Callahan. “Rigs-to-Reefs is definitely not save the whales. It’s not as easy. It’s not as digestible. But if you dig a little deeper, there’s a lot of really interesting science there, and a lot of interesting pathways to go down.”

Brittany Hook is communications coordinator at Scripps Institution of Oceanography. This article originally appeared on the Scripps Institution of Oceanography website: www.scripps.ucsd.edu