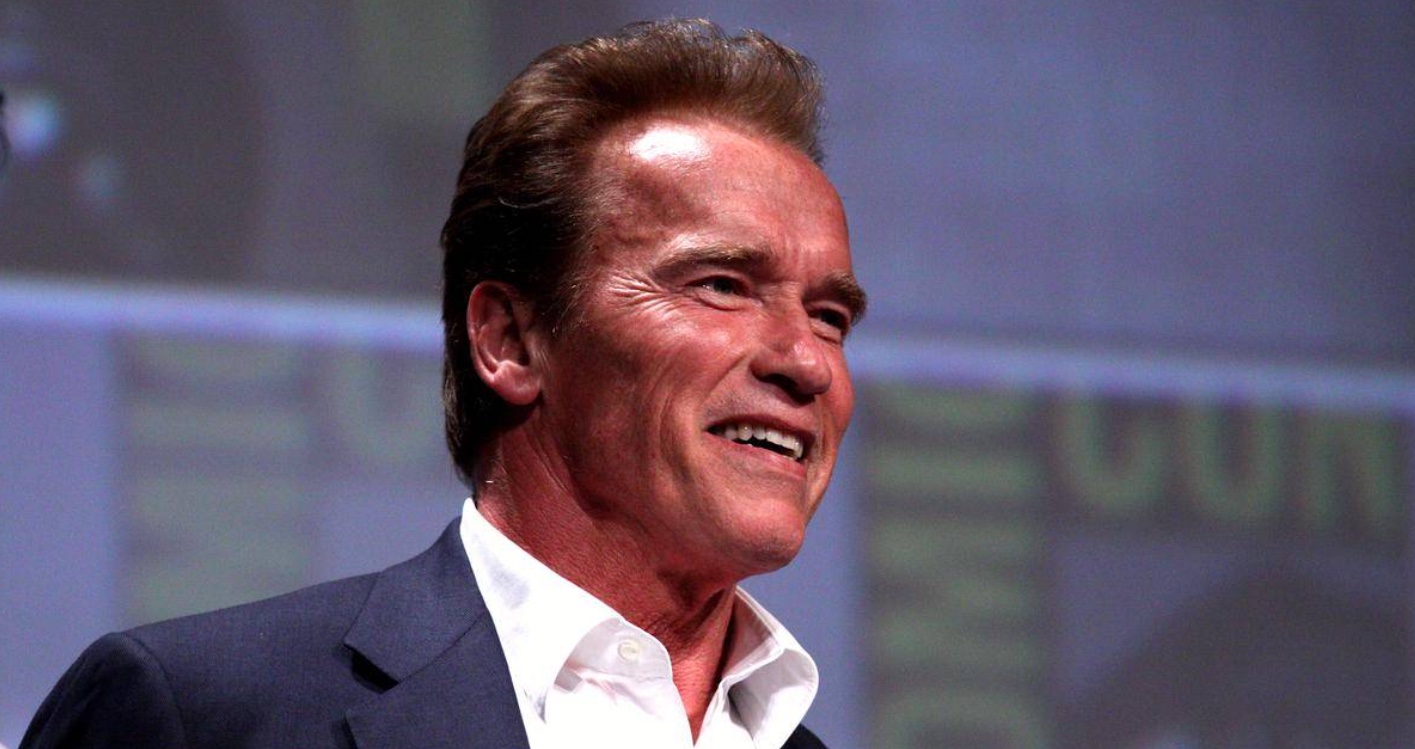

Cover Story — April 2012

Social Network Guru

UCSD professor reveals the power of human connections

By Delle Willett

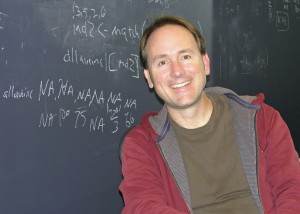

James Fowler’s elementary teacher wrote on his report card, “Does not play well with others.” Thirty years later, playing with others is what James does best.

James Fowler grew up in a small Oklahoma town, not very happy. Even though he had a very supportive family, he never felt connected to his peers. “I was such a big outlier in terms of the things I was interested in.” Add to that, the town was very religious and critical of his lack of participation in religious activities. “They told me I was going to hell.” By the time he went to Harvard, Fowler had the attitude: “I don’t need anybody. The group was just designed to bring me down.”

Today, at 42, and living in Mission Hills, his life is a social network story; he’s an expert on the power of human connection. “Now I always collaborate,” he says. “It’s rare for me to do things on my own. And part of that transformation was realizing that this radical individualist, Robinson Crusoe, is wrong. We have to consider that all our strengths are not only for ourselves but for the benefit of others.”

A UC San Diego professor in the Political Science Department and Medical Genetics Division, Fowler is a new kind of political scientist who pushes the boundaries of his field to identify social and biological forces that underlie human nature. He is well known for his research on the evolution of cooperation, behavioral economics, political participation and genopolitics.

Being Transformed

While doing his undergrad studies at Harvard (1988–92), Fowler began working with, and bouncing ideas off others. But his real transformation kicked in when he met Harla Yesner in 1992, first his Peace Corps co-worker, then his girlfriend, now his wife, the mother of his two young sons, an educator, and his very best friend. Harla helped him see the wisdom in collaborating with others and in diversifying and expanding his circle of friends and acquaintances.

The next milestone was when Fowler’s adviser at Harvard grad school introduced him in 2002 to Dr. Nicholas Christakis, who was interested in how illness in one person might cause illness in another. At the time, Fowler was studying the origins of people’s political beliefs and examining how one person’s attempt to solve a social or political problem influenced others.

They traded papers and started developing data. Over the next seven years Fowler and Christakis collaborated on scientific research that resulted in the publishing of “Connected: The Surprising Power of Our Social Networks and How They Shape of Lives,” in 2009.

Three Degrees of Influence

In this book, the authors argue that, while people are connected to each other on average by six degrees of separation, the spread of influence in social networks obeys what they call the “Three Degrees of Influence Rule.” Everything we do or say tends to ripple through our social network, having an impact on our friends, our friends’ friends and our friends’ friends’ friends. Likewise, we are influenced by friends within three degrees, and generally not by those beyond.

Social networks have value because they can help us to achieve what we could not achieve on our own. “They spread happiness, generosity and love,” the authors say. “They are always there, exerting both subtle and dramatic influence over our choices, actions, thoughts, feelings, even our desires. And our connections do not end with the people we know. Beyond our own social horizons, friends of friends of friends can start chain reactions that eventually reach us, like waves from distant lands that wash up on our shores.”

After the book was published, Christakis was named as Time magazine’s 100 most influential people in the world and Fowler was on the “Colbert Report.” Their research findings have been featured on “The Oprah Winfrey Show,” “Good Morning America” and the “Today” show, and on the front pages of The New York Times, the Washington Post, the Los Angeles Times, the Chicago Tribune and USA Today. They are now working on a prospectus for a second book and are, says Fowler, “joined at the hip.”

Opening New Doors

Doing the research for and writing Connected has completely changed Fowler’s life. “I never like to use the word ‘famous,’ but as famous as some random professor can be, I’ve run into people who have read the book and they are excited to find out that I’m the person who wrote it.”

“One of the things we talk about in the book is that you can’t really understand what’s going on online until you understand real-world, face-to-face social networks,” says Fowler. “And so we have a unique message that has given me a lot of opportunities to talk to people from a wide variety of backgrounds about how important social networks are. ”

For example, there are a lot of people in business now who are really interested in Fowler’s opinion about things that are going on online. He’s been invited to the Microsoft CEO Summit, having dinner at Bill Gates’ house with him, Warren Buffet and 100 other CEOs around the country. “And that would never had happened to me without having written the book,” Fowler says. “It’s given me a little notoriety that gives me access to a lot of things I wouldn’t have had access to before. So now I’m working directly with Facebook and the head of the Data Science Team there, and I’m sure that’s partly because of my ability to make all of these ideas accessible for a broad audience.”

Socializing Science

At UC San Diego, Fowler attracts “amazing grad students who come to me with new ideas and I just sit back and let them drive. ”

He works one-on-one with students on their projects for about 10 to 15 hours a week. “I know that science is a social enterprise so I also try to make my teaching social. Make it fun. We have lunch once a week — eating around the campfire is really an important experience for human beings —and develop social bonds, because those bonds lead to people exchanging ideas and to collaborations — the most important things you can do in science.”

Understanding Social Networks

“The networks we create have lives of their own,” say the authors. “They grow, change, reproduce, survive and die. Things flow and move within them. A social network is a kind of human superorganism, with an anatomy and a physiology — a structure and a function — of its own. Our local contributions to the human social network have global consequences that touch the lives of thousands every day and help us to achieve much more than the building of towers and the destruction of walls.

“If we do not understand social networks, we cannot hope to fully understand either ourselves or the world we inhabit. Understanding social networks allows us to understand how, in the case of humans, the whole comes to be greater than the sum of the parts. Just as brains can do things that no single neuron can do, so can social networks do things that no single person can do.”

Keeping and Making Friends

After learning about the “Three Degrees of Influence Rule,” someone may come to the conclusion that they should carefully select and weed out friends when those friends are picking up bad and unhealthy habits, or becoming obese.

Well, not so. Specifically in the case of obesity, one of the things the authors found was: the people who kept their friends who became obese were actually healthier than the people who dropped their friends who became obese. “The moral of the story is, Don’t dump your friends. When you have a friend who is struggling with health problems or struggling with something negative in his or her life, the first thing you should do is try to help him deal with that problem—benefiting both of you,” advises Fowler.

What Fowler found most true while researching is the power of human connection. “We’ve actually been able to show through scientific method that the things that we concluded were true are actually true. And for me, the thing that is most extraordinary is scientific proof that there are people in the world who you don’t know and have never met who are influenced by your actions. And I personally think that just teaching people that that’s the way the world works is going to increase the responsibility that we take in terms of the people we are connected to.”

Marginalizing People

What surprised Fowler the most was “the nice twists and turns that came up with each of our studies. As scientists, we are looking for things that are always true, and so we are always trying to see the unity, the general law.” And what they saw, with the complexities of social networks, in the obesity studies for example, is that adults who have become overweight do not have their ties cut to friends and family, but smokers do get pushed to the outer fringes which polarizes them, making it harder and harder to reach the smokers to help them change the behavior.

“I feel sorry for smokers because at the same time we’re using public-health campaigns to make other people physically healthier, we’re making a smaller group of people socially less healthy,” says Fowler. “And what our research shows is that when you disconnect people they become less healthy. And the last thing we want is to ostracize the very people we are trying to help.”

Connecting to Voters

Given his reputation for using lots of different creative methods to figure out how voters and parties affect each other, President Obama’s campaign recently invited Fowler to help with analytics for the re-election campaign. Fowler says that Obama’s first campaign was a historical milestone in all kinds of ways; yet the most revolutionary was not his remarkable ability to connect with voters — it was his ability to connect voters to each other. A fundraising juggernaut, Obama’s campaign took advantage of the power of online social networks and social (person-to-person) media.

Believing in God

On the subject of religion, Fowler says, “I have a feeling, in part, that religion makes us more connected and this connectedness has helped us to survive. So rather than telling people to believe differently than me or that they should stop believing in God, I’m much more interested in knowing why they believe in God and in trying to figure out what the benefits are. I think we have reached a point where it’s possible to have tolerance for people who have different beliefs and to place value in these beliefs in terms of keeping us connected.”

Realizing the Most Important Thing

Our connections affect every aspect of our daily lives. How we feel, what we know, whom we marry, whether we fall ill, how much money we make, and whether we vote all depend on the ties that bind us.

While it’s true that there are always people out there who do things that ripple to you, you also have the capacity to achieve in your own life what will make you, and your friends and their friends’ friends better off.

“Realizing that you have network power is probably the most important thing you can do in your life,” says Fowler.