Discovering the ‘lost’ architect of Rancho Santa Fe: Lilian Rice

Historian and journalist Diane Welch uncovers the fascinating life and work of one of the San Diego region’s most significant architects

By Ann Jarmusch

When truck drivers went on strike at a Rancho Santa Fe construction site in 1923, Lilian Rice rounded up three colleagues. Each of the four women climbed into a driver’s seat and got the trucks rolling again.

When Rice received top design honors from the American Institute of Architects’ San Diego chapter, she was its only female member.

And when she specified “old and weathered” ceiling beams for a Spanish-style hacienda she designed in Escondido, she stopped the workmen from distressing the lumber with torches and tools. She directed the crew to “build a huge bonfire” to char the beams, then go over them with wire brushes.

“That’s the only way you’ll get that weathered look, like they’ve been washed around in the sea or just laid out on Palomar Mountain somewhere,” Rice said, according to Mildred Finley Wohlford, the client who witnessed the scene.

Lilian Jeannette Rice, who was born in National City in 1889 and died in Rancho Santa Fe in 1938, deserves widespread acclaim as an architect and leader who thrived during the Great Depression. More than a few of her residential and commercial buildings in Rancho Santa Fe, La Jolla and elsewhere are listed as national or local historic landmarks.

A graduate of the University of California at Berkeley’s architecture program, Rice is best known for her low-slung, Spanish-Andalusian-style homes (with plain stucco or adobe exteriors) that ramble around courtyards with fountains. Elaborate beamed ceilings in thick-walled living rooms are one of her hallmarks — and a link to the Arts & Crafts Movement.

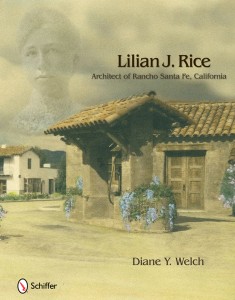

At last, Rice is receiving recognition beyond Southern California, thanks to the international release of the first book on her life and career. Diane Y. Welch, a historian and journalist who lives in Solana Beach, recently published the richly illustrated “Lilian J. Rice: Architect of Rancho Santa Fe, California” (Schiffer, 224 pages, $49.99) and launched the Website: lilianjrice.com.

“I wanted to bring her out of the shadows,” Welch said in an interview.

The book does that and more. Filled with vintage and contemporary photographs, it’s a book that will appeal to many audiences, especially designers and homeowners looking for ideas or authentic architectural details, from tiles to lanterns. Lovers of the California Dream will appreciate Rice’s affinity for Southern California’s history, mix of cultures and topography. Young girls aspiring to be architects or developers will read it and forge ahead, while students of women’s history and architecture will dive into its extensive and often fascinating academic notes.

Those who know about Rice’s work associate her with the town planning and custom residential design of Rancho Santa Fe, the wealthy enclave in North County that studiously retains the Spanish Revival and adobe rancho-style rural charm Rice crafted for years beginning in the early 1920s.

That’s when Rice’s renowned employer, San Diego architect Richard Requa of Requa and Jackson, evidently turned over this major project to her. Proving her design talent, organizational abilities and people skills again and again, Rice rose in the estimation of her client, the Santa Fe Land Improvement Company, as well as Requa. Eventually, she opened her own successful architecture practice in Rancho Santa Fe, undertaking projects throughout San Diego County.

Welch lists about 170 of Rice’s projects in the book, including some that were never built. She believes there are more to be discovered. (Unfortunately, the book’s list does not include any addresses, a nod to some owners’ insistence on privacy.)

“She epitomized the modern career woman 80 years ago or more, 100 years ago,” Welch said. “She was an overachiever who continued to study and improve herself, but she also knew how to have fun.”

Welch was researching North County about five years ago when she noticed Rice had two major commissions in 1936: the Paul and Magdalena Ecke home in Encinitas and San Dieguito Union High School, a Works Progress Administration project. It was unusual to find a woman architect in that era, let alone one with her own firm and prominent buildings to her credit.

“I thought, ‘This woman is significant in history,’” Welch recalled. That day, June 12, 2005, she made a note in her journal, pledging to research and write about Rice. A library search turned up no books on the architect, but Welch did discover June 12 is Rice’s birthday.

While the author interpreted the date as an encouraging sign to write the biography, Welch couldn’t have known it would be such an arduous task. Sadly, apart from some architectural renderings, blueprints and ephemera, few records about Rice’s post-college years and professional life survive. (Even her gravestone is engraved with the wrong birth year. Only one page of her journal, circa 1912, exists, according to Welch, who reproduces it in the book, where it demonstrates Rice’s sense of humor and adventure.)

As a result of this vacuum, Rice has been unfairly overshadowed in some quarters by Requa, who was one of San Diego’s finest residential designers, architect of the 1935-36 California Pacific International Exposition in Balboa Park and a popular man about town.

One of Welch’s most important findings that supports Rice’s central role at Rancho Santa Fe is a 1976 interview with San Diego architect Sam Hamill. He also worked for Requa and was assigned to Rice’s field office (she was the “resident supervisory architect”). Hamill said Rice “should receive the major credit” for laying out Rancho Santa Fe’s quaint, oval civic center.

“Miss Rice was a very responsible person,” Hamill added. “She didn’t in any sense of the word supplant her employer. It’s simply that her meshing with the whole Santa Fe (Land Improvement Company) program was so direct and was so satisfactory … and the ranch was sufficiently far away” from Requa’s downtown San Diego office that it wasn’t profitable or practical for him to be directly involved.

Welch also found a 1923 Los Angeles Times article that raved about Rice’s stature in Rancho Santa Fe. “People planning handsome country homes consult her. The Spanish garden which transformed the garage in the civic center into a piece of artistic beauty (which appears on the book’s cover) was her idea. She is familiar with every bit of construction work in the 20 square miles of the project.”

Welch spent four years researching Rice, tracking down vintage photographs, coordinating new photography and finding young designers to recreate Rice’s architectural renderings and floor plans. She sought out or befriended Mim Sellgren, a Rice relative; Tom Clotfelter, a Rancho Santa Fe fixture and real estate agent; owners and historians of Rice-designed homes; and members of the ZLAC Rowing Club in Pacific Beach, where Rice was vice commodore and the architect of the club’s 1932 wood building.

“I camped out at the National City Library, reading the newspaper on microfilm. Rice often appeared in the society column — but in just a sentence or two. I call these ‘1920s tweets.’” Welch said.

Calling her efforts “a treasure hunt,” Welch still isn’t satisfied. Now that her book is out and she’s using social media to promote it, new information is coming to light. Recently, for example, a woman who lived in the Rice family home after Lilian’s brother sold it contacted Welch via Facebook. The house has since been demolished, but the woman told tales of intriguing belongings the Rices left behind.

Welch can’t wait to meet her to hear and perhaps authenticate more facts about Lilian J. Rice — the woman she once dubbed “lost architect” and vowed to deliver from history’s shadows.